Civil Rights For Beginners (2016).

Paul Von Blum. Illustrations by Frank Reynoso, et. al.

Foreword by Peniel E. Joseph.

Danbury, CT: For Beginners Books.

ISBN-10: 1934389897; ISBN-13: 978-1934389898.

161 pp., $15.95.

Malcolm X For Beginners (1992).

Text and Illustrations by Bernard Aquina Doctor.

Danbury, CT: For Beginners Books.

ISBN-10: 1934389048; ISBN-13: 978-1934389041.

186 pp., $16.99.

Black Panthers For Beginners (1995).

Herb Boyd. Illustrations by Lance Tooks.

Danbury, CT: For Beginners Books.

ISBN-10: 193999439X; ISBN-13: 978-1939994394.

154 pp., $15.95.

Fanon For Beginners (1998).

Text and Illustrations by Deborah Wyrick, Ph.D.

Danbury, CT: For Beginners Books.

ISBN-10: 1934389870; ISBN-13: 978-1934389874

184 pp., $15.95.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party. Although the Black Power movement officially began months earlier, with Stokely Carmichael, stalwart of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, publicly using the term in Alabama, for this writer the Black Power movement started when two brothers met in Oakland and, borrowing a symbol that SNCC was politically organizing with, developed a 10-point program for Black liberation. Under Carmichael, SNCC stood with the Congress of Racial Equality as the Black Power wing of the Freedom Movement, with an emphasis on organizing Black people to see themselves as members of self-determining Black communities, of miniature Black/African nations in the land of the thief, home of the slave.

Providing art and information to The People—like Fannie Lou Hamer, formally uneducated but politically astute—was a priority for the Black Power Movement. Africana Studies, an idea that had just begun to be implemented in American academia, was still being written in the streets in blood, footnoted with broken glass and Molotov cocktails.

The “For Beginners” books series, originally published by Writers and Readers, are books for The People. The company describes what it produces as “documentary comicbooks.” Being a little more precise, what they create, actually, are well-researched introductory books about complex topics and personalities illustrated by drawings that oftentimes mimic comicbook style. These four books listed were chosen to highlight and celebrate the Black Power movement through their collective analysis and unique presentation. (Although, it is known that this idea is far from new: the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a white liberal group, published “Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story” in 1957, and Julian Bond published an anti-Vietnam comicbook targeting the Black community ten years later.)

The publisher allows description and explanation on its authors’ terms. Von Blum’s book, for example, takes the entirety of Black history and describes it through the lens of the Civil Rights Movement, reminding the reader that Ida B. Wells sat down and refused to move on a train before Rosa Parks was even a gleam in one of her parents’ eyes. It mentions unheralded actors such as the Southern Tenants Farmers Union, which held a sit-in in the U.S. agriculture secretary’s office in 1934. Doctor’s book on Malcolm is a wonderful text-collage combo (done in the pre-digital era!) that is not afraid to go for the symbolic image: seeing a tiny Malcolm being held in the palm of “The Autobiography of Malcolm X”’s “Sophia” (Bea), his white lover, makes the statement. Doctor provides an impressionistic history of Malcolm—a story of Black ideas that override chronology (and unfortunately, sometimes biographical facts) and ideological complexity.

Out of the four, the two that stand out overall are Boyd’s BPP and Wyrick’s Fanon. Wyrick blasts the complex Fanon into understandable chunks of intellectual peanut brittle, explaining and dissecting, critiquing and footnoting. Her thoughtfulness, care and talent shows through, since her own illustrations do a wonderful job of supplementing and complementing her deceptively simple text. Her closing chapter on Fanon’s multifaceted legacy, and her beautifully crafted first-person epilogue, is alone worth every tree that was sacrificed to make this book. Boyd’s snappy, bouncy prose style is more than equaled by Tooks’ energetic, playful art. (This reviewer wishes that the publisher would have made Von Blum follow the Boyd/Tooks model, instead of providing dry, trying-to-get-tenure academic text punctuated by even drier art by the Civil Rights book’s main artist, Reynoso. Liz Von Notias, sadly a supplementary artist for the text, provides the narrative’s more vibrant, alive drawings.) Boyd quotes from most of the Panther scholarship that existed at the time of publication, creating a mosaic of first-person recollections from Panthers as well as its public enemies and private informants. The sections on sexism within the BPP and the Huey Newton/Eldridge Cleaver split is very strong, as is the tracing of police plant Gene Roberts from Malcolm X’s Organization of Afro-American Unity to the Panthers.

With the exception of Von Blum’s Civil Rights, which was published this year, the major problem with these books is that they desperately need updating. For example, at least a score of studies, anthologies, memoirs and biographies have been published on the Black Panther Party since Boyd and Tooks, and Boyd himself is the co-editor of “The Diary of Malcolm X,” a 2014 book that, like “Blood Brothers,” the recent Randy Roberts/Johnny Smith narrative history on Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, must be incorporated into Doctor’s almost 25-year-old “For Beginners” text. The books also can be editorially uneven; for example, some titles have indexes and some don’t. That sloppiness should not be tolerated.

In spite of these flaws, these books need to be supported by The People. (With the eight-year White House national experiment with being adjective-less “Americans” almost over, it’s time for Black America to go back to its socio-historio-cultural basics.) They need to be purchased and passed out to the Black masses, of any age, who, like the high school seniors and college freshmen the “For Beginners” series is apparently targeted to, may be intimidated by “serious,” “scholarly” texts. Google Search, Wikipedia and YouTube need not have the first, and last, word when it comes to African/Black leaders and movements. As unlikely as it seems, mass political education of The People might only be a few million “documentary comicbooks” away.

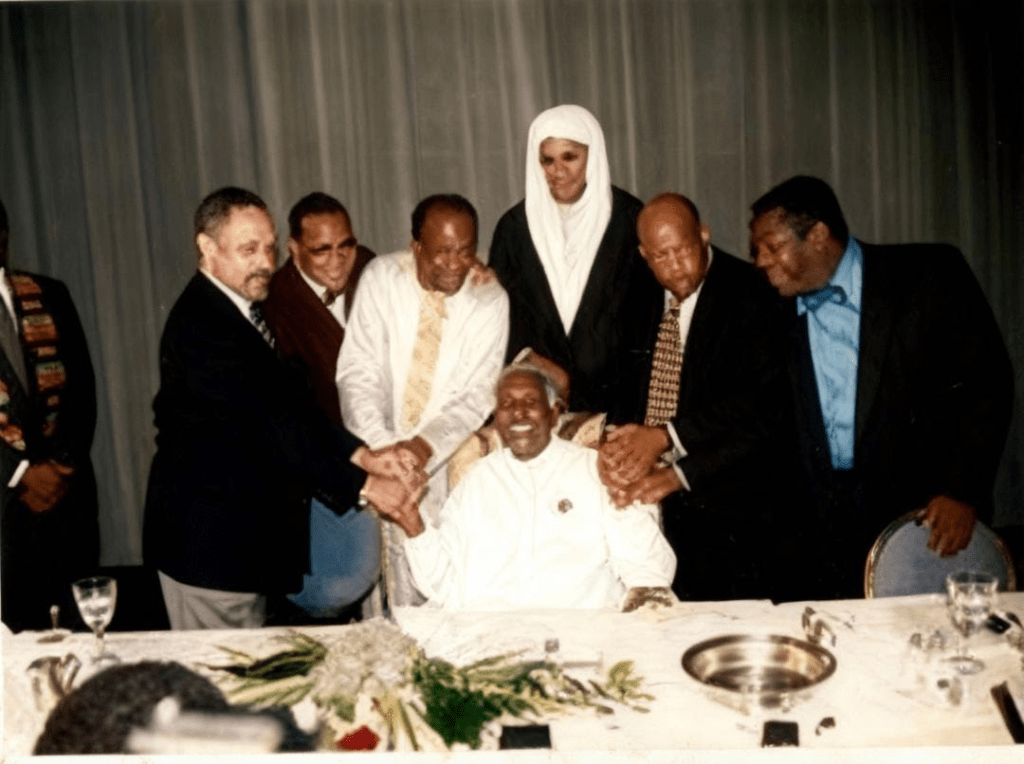

JAMIL AL-AMIN aka “H. RAP BROWN”October 4, 1943 – November 23, 2025

JAMIL AL-AMIN aka “H. RAP BROWN”October 4, 1943 – November 23, 2025