Weekly Column

Thursday, August 21, 2025

By Amy Goodman & Denis Moynihan

On Tuesday, President Trump attacked the narrative long taught in US schools and documented in museums, about the abhorrent, centuries-long practice of slavery. He focused on The Smithsonian Institution, the world-renowned center of learning and culture based in Washington, DC.

Trump wrote on his social media platform, “The Smithsonian is OUT OF CONTROL, where everything discussed is how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was.”

“How bad slavery was.” It is simply unbelievable that such a statement could be uttered by a president in 2025. Yes, slavery was bad, President Trump. It was evil and remains a stain on this country. We should never stop talking about it.

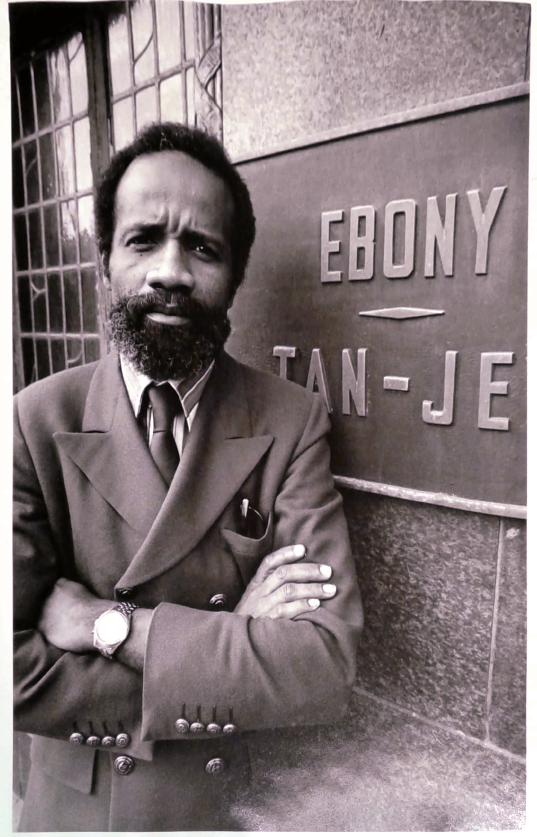

Lonnie G. Bunch III is the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian, overseeing the entire institution. Prior to that, he was the co-founder of the Smithsonian’s internationally renowned National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Democracy Now! interviewed Bunch in February, 2020, just before the pandemic struck. Bunch described the importance of depicting slavery:

“One of the most important things for me was to talk about the slave trade…I felt that we had to find real remnants of a slave ship,” Bunch said.

“We found the São José. It was a ship that left Lisbon in 1794, went all the way to Mozambique and picked up 512 people from the Makua tribe, was on its way back to the New World when it sank off the coast of Cape Town. Half of the people were lost. The other half were rescued and sold the next day.”

Bunch recalled Trump’s visit to the African American Museum in 2017, at the beginning of his first term as president:

“The first place Donald Trump visited in an official capacity was the museum. I think he was stunned by the stories we told, and there was so much he didn’t know,” Bunch said. “What I realized is that if people who didn’t know but had political influence could come through the museum, I could help them understand, hopefully, something that would change the way they did it.”

Given Trump’s new assault on The Smithsonian, it seems his visit to the African-American Museum didn’t have Lonnie Bunch’s hoped-for uplifting impact.

In late March of this year, Trump issued an executive order targeting the museum conplex. The order alleges that “the Smithsonian Institution has, in recent years, come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology.” The order further creates a committee to review the contents of exhibits for “improper ideology.”

Trump has set the tone, normalizing the rejection of history, of the indescribable horror of slavery in the United States. His loyalists follow suit.

In 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis promoted a revision to the state’s school curriculum, to include instruction on “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their own personal benefit.” DeSantis defended the offensive guidelines, saying “I think that they’re probably going to show some of the folks that eventually parlayed, you know, being a blacksmith, into doing things later in life.”

Trump’s Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth recently joined a growing Christian Nationalist congregation. The church’s co-founder, Doug Wilson, has written that slavery “produced in the South a genuine affection between the races.” Hegseth has ordered that previously removed statues of Confederate officers be put back, and is restoring Confederate names to military installations that had been recently removed.

The National Park Service has announced that the only outdoor statue in Washington, DC honoring a Confederate, Albert Pike, which was removed following the racial justice protests of 2020, will be restored. Pike was a Confederate general and alleged member of the Ku Klux Klan.

And as Trump has successfully defunded public broadcasting, some are advocating that PBS content be replaced with material from the rightwing media company PragerU. In one clip from Prager already being used in 10 states, an animated cartoon Christopher Columbus is shown downplaying slavery:

“Being taken as a slave is better than being killed, no?”

Annette Gordon-Reed, professor of history at Harvard University, president of the Organization of American Historians and Pulitzer award-winning author, said on Democracy Now!, “It’s an attempt to play down or downplay what happened in the United States with slavery…This is a whitewashing of history.”

With Trump’s all out assault on truth, learning, and the institutions that preserve and curate our collective history, places like The Smithsonian Institution are more important than ever.

“In the era of Donald Trump,” Bunch concluded in 2020, “the museum has become a pilgrimage site, a site of resistance, a site of remembering what America could be, and a site to engage new generations to recognize they have an obligation to make a country live up to its stated ideals.”

The original content of this program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. Please attribute legal copies of this work to democracynow.org. Some of the work(s) that this program incorporates, however, may be separately licensed. For further information or additional permissions, contact us.