Black media institutions/forums don’t have the funds to create advance obits. So this will clearly function as one of them.

https://stateofblackamerica.org/authors/dr-ron-daniels

*******

REQUIRED READING ON THE TOPIC BY AMIRI BARAKA:

**********

Black media institutions/forums don’t have the funds to create advance obits. So this will clearly function as one of them.

https://stateofblackamerica.org/authors/dr-ron-daniels

*******

REQUIRED READING ON THE TOPIC BY AMIRI BARAKA:

**********

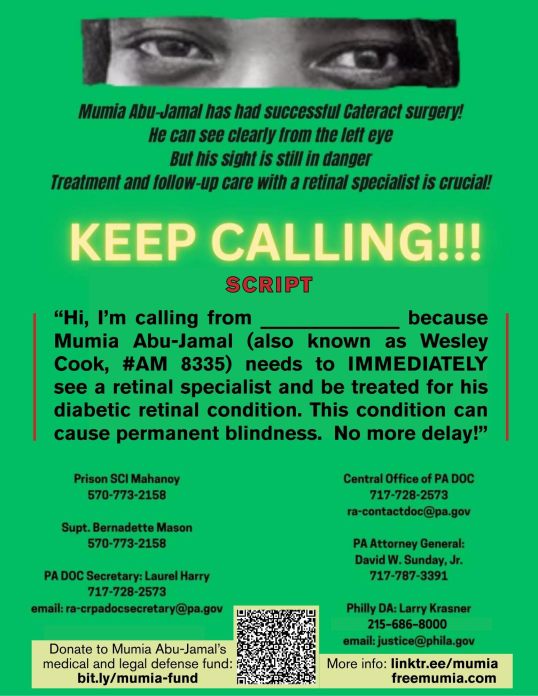

This week on CounterSpin: With some 2 million people in prison, jail or detention centers, the US is a world leader in incarceration. Ever more people disappear behind bars every day, many for highly contestable and contested reasons. But despite age-old rhetoric about prison as “rehabilitation,” US journalists say—through their work—that if any of the criminal legal systems in this country decide to punish you, that’s proof enough that you should never be heard from again. With some exceptions for celebrity, corporate journalists seem absolutely OK with silencing the huge numbers of disproportionately Black and brown people in prison. It’s a choice that impoverishes conversation about prison policy, about public safety, and about shared humanity.

There are reporters and outlets paying attention—and willing to navigate the serious barriers the prison system presents. One such outlet is Prison Radio, actually a multimedia production studio, that works to include the voices of incarcerated people in public debate.

It’s thanks to them that we have the opportunity to speak with journalist, author and activist Mumia Abu-Jamal, whose 1982 conviction for the killing of a Philadelphia police officer showcased failures in the legal system, yes, but also exposed flagrant flaws in corporate media’s storytelling around crime and punishment and race and power.

Janine Jackson: When our guest turned 71 in April, his organized advocates acknowledged the day with mobilizations around how US constitutional law is “weaponized to repress dissent and create political prisoners,” with public discussion about activism on campuses around Palestine, and about the importance of public protest and brave speech.

The 1982 conviction of Mumia Abu-Jamal for the killing of police officer Daniel Faulkner followed a trial marked by prosecutorial and police misconduct, purported witness testimony that was shifting and suborned, discriminatory jury selection, and irresponsible and frankly biased media coverage, which hasn’t changed much over years of court appeals and continued revelations. It was and continues to be clear that, for powers that be, including in the elite press, it is important not only to keep Mumia Abu-Jamal behind bars, but to keep him quiet.

It hasn’t worked. Despite more than four decades in prison, our guest has not ceased to speak up and speak out, on a range of concerns well beyond his own story, with the support of advocates around the world. He joins us now. Welcome to CounterSpin, Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Mumia Abu-Jamal: Thank you for inviting me.

JJ: Well, you never know what folks are learning for the first time. So I just wanted to start with noting that you are a journalist. Mumia, listeners should know, was a radio reporter at various Philly stations. He was head of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists.

I sometimes think, once you’re a witness and a storyteller, you can’t turn that off, even if you become the subject of the story. Certainly you have never really stopped doing what you started out to do, have you?

MAJ: I have not. I guess old habits die hard.

JJ: So you’ve continued to listen and report and to speak from whatever position you’re in, because a journalist is what you are, yeah?

MAJ: Yeah. But in a cultural sense, I think of myself as a griot, probably a progressive griot, but a griot nonetheless. In African culture, griots were the people who remembered the history of the tribe, and, really, they served the prince in power, but they served the tribe as well. And there’s an old tradition that’s talked about in Senegal that when a griot dies, you don’t lay him in the ground. You bury him vertically in a tree, so that he and his stories are remembered.

I think about telling the stories of a different kind of tribe here in America, a tribe of rebels, a tribe of people who struggle, a tribe of the poor and the oppressed, because those are the stories that rarely get heard and get reported in much of the world.

JJ: That leads me directly to what I just saw on Wikipedia, which said:

From 1979 to 1981, he worked at National Public Radio affiliate WHYY. The management asked him to resign, saying that he did not maintain a sufficiently objective approach in his presentation of news.

And, yeah, it gives me a giggle. And I think that while news media has, in important and life-altering ways, gotten much worse since then, there is, in some places, anyway, a growing recognition that objectivity is a myth, and a harmful one, and that we are all enriched by reporters who can bring their whole selves to the job.

MAJ: If you’re not bringing your whole self to the job, you’re not doing the job. And I think that this whole objectivity myth began when the art of journalism—I won’t call it a science—but the art of journalism was professionalized.

And before that, of course, the media was a very political entity. I remember reading in a history book, it might’ve been Howard Zinn or something like that, a New York newspaper called the New York Caucasian. I mean, think about that. Papers were printed by unions and churches and other kinds of groups, and it was reflective of the people who printed it, not the people who paid them, because journalism was more of a work that people loved doing than a quote unquote “profession.”

Howard Zinn warned us about the dangers of professional distance in many fields. As an historian, of course, Howard Zinn learned history, not when he earned his PhD at Columbia, but when he was teaching at a Black college during the civil rights years, and he was teaching pre-law, something like that, and he was telling people at the school about how the Constitution protected them, and they had certain rights. They said, “Excuse me, Professor Zinn, what are you talking about?” And he said, “Well, you have the right to do this and do that.” They said, “We don’t have the right to vote down here.” He said, “What are you talking about?” They said, “We go to the voting office, they will beat us up.” He said, “Who will beat you up?” They said, “The cops and everybody else.”

So Howard Zinn followed his students to the voting place, and he sat and he just looked, and he learned something that he had never learned in college—and this was Atlanta, of all places—that when people tried to register to vote, they were refused. They had these ridiculous tests they gave them, and if they did not walk away, they would be beaten and locked up.

And so Howard Zinn learned that which the profession did not teach him, that history isn’t always written in these documents or in books. They’re lived by people, and we have to pay attention to how people live in the real world to tell their stories.

JJ: What I get from that story is that an article can tell you the law says this, and that’s not the same thing as telling you how the law is lived out in various people’s lives.

And we have a journalist right now, there are many, but I will just say Mario Guevara, who apparently has an Emmy award, but it’s not enough to prevent his having been detained for over a hundred days now, for the work of live streaming law enforcement activity, including ICE raids. So we have a journalist doing what a lot of other journalists would say is what they’re supposed to do, and he’s been detained.

So when people hear generically about “journalism is under attack,” well, no, it isn’t all journalism that’s under attack. It’s a particular kind of witnessing.

MAJ: That’s actually true, but also think about, in this era, in this time, and I’m speaking right now about the, shall we call it the Kimmel affair, and how everybody is talking about First Amendment rights, the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press. The case you described is the unfreedom of the press, where a journalist is captured and caged for telling stories and streaming stories about government repression. Who do you think gives a damn about the Constitution, the government or the people?

JJ: Let me ask you, continuing with media, I think people read the data point, “Oh, 2 million people incarcerated in the US,” more and more every day being put in detention centers, and they’re shut away from families and friends, by procedure, by distance, but also shut out of public debate and conversation.

And I think there’s a feeling that this is a cost to those people who are imprisoned, but there’s less recognition that there’s a cost for everyone when we don’t get to hear from this ever-expanding and various group of voices. And I think journalists who buy into, wittingly or not, the idea of “out of sight, out of mind”—they’re serving someone, they’re serving something, by excluding the voices of the incarcerated in our public conversation.

MAJ: Well, yeah, they’re excluding not just the imprisoned, who, as you said, are in the millions in the United States, but also they’re excluded from thinking about what it means to be truly American, because this is part of that. There is no space in the American landscape where the shadow of the prison doesn’t fall.

And that’s because it is so huge. It is so vast that it impacts those within and without, because everybody in prison has someone on the outside of prison that loves them or they love: their children, their mates, their parents, you name it. And that shadow falls on all of those people. There are stories that can enrich our understanding of what it means to be human by allowing people in this condition to be heard as full human beings.

JJ: And I blame media a lot. I mean, I’m a media critic, but I also, as a media reader—media disappear people, as well as the state disappears them. Suddenly they move into another column, and are no longer worth hearing from. And I don’t know that people understand how much we lose when that happens, and how much media are feeding into this oppressive regime by underscoring the idea that once people go behind bars, we don’t even need to think about them at all anymore.

MAJ: We call the media the Fourth Estate, don’t we? But it’s an estate of what?

JJ: Right? For whom?

MAJ: The estate is part of the state. It’s not part of the people. And as long as people think in those terms, those elevated and false terms, then it’s difficult for them to relate in a human way to people who are in a distressed situation.

And you can’t talk about media without talking about power, because you know and I know that much media is about sucking up to power. I am reminded of, I think it was in the book Into the Buzzsaw that I read years ago; it was about forbidden stories that reporters got fired for, all around the spectrum. I mean, Fox News stations, all kinds of newspapers and whatnot. But the real key is that when people began telling stories that their editors and their bosses didn’t like, well, they got disappeared. By that I mean, of course, they got fired or threatened with firing.

But one of the things that really touched me in this context was that a reporter was talking about how journalists could never say that the president, for example, was lying. And they said, “Well, why not?” And people from the audience were like, “Why don’t you say that?” “Well, we are taught and we’re trained never to say that.” Well, then what if you hear him, and he’s lying, you just act like you don’t hear him? You’re just carrying his lies. That’s the relationship between the media and power. I think that began to crack around the time of the Bush years. But look where we’re at right now. We’re in a whole new world.

JJ: Just rocketing into the past, just rocketing backwards past so many gains that we thought we had made. And I remember that conversation well, and when the audience started saying, “What do you mean you can’t say the president’s lying?” the reporters said, “Well, we think it’s more powerful to say the president’s statements did not comport with information as we have it…” They had this kind of painful, tortured thing that they told themselves was somehow more impactful. So there’s a culture inside newsrooms that gives them, like, 12 degrees of difference between themselves and the truth.

But we know that other folks know what we know, are as irritated and disgusted and seeing through the emperor and his no clothes as we have. And so we have independent media growing up. And I just wonder, when you see the media landscape, do you see hope in these independent journalistic outfits that are coming up? Do you see Black-owned, some of them Black-centered, journalistic organizations sprouting up? Is that a source of hope?

MAJ: I think it can be. But the real question is, how will the sandwich taste once everything comes together? And when I think of a great journalist, I think of somebody like Chris Hedges, who was asked to join the New York Times. He didn’t go the regular route, where most reporters kind of prayed for an opportunity to write for a paper like the Times. He was in seminary, and he began hearing about El Salvador, and he went down there and he saw things and he began writing about it, and people were reading his stuff, and the Times came and said, “Boy, you’re a great writer. Can you write some articles for us?” And he was like, “OK, yeah, why not?”

Of course, all of that changed around the time of, I think it was 9/11 and the Iraq War. And Chris did a speech, and he got up and he talked with people and he was telling them, saying, “Listen, do not let these politicians use your fear to get you involved in a war.” And people began singing “God Bless America” and yelling at him, because they didn’t want to hear it. And it was almost like Chris was seeing which way the wind would blow.

And he got threatened by his editors, like, “Oh, that’s one strike against you, buddy.” I mean, he could care less. Again, he didn’t, like, run and get the job. They ran after him, because of the clarity and power of his writing.

JJ: But then that clarity and power was just what they didn’t want, actually, to hear.

MAJ: Exactly. Well, I think the scholar Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò hit the mark when he said it’s “elite capture.” He had been captured by the Times, and they had a tiger by the tail. And Chris really could care less because, in the new media world, he writes online, and probably is more read today than he was when he was at the Times.

JJ: Absolutely, and that’s kind of where we’re at, where folks who want to do reporting, who want to witness, but who are not willing to accept the constraints of corporate news media, we haven’t quite built the structures for those folks to have a platform, for those folks to be heard from. So we’re kind of in transition, in terms of media structures. But I do believe that, in terms of audience, more people are recognizing the failures and the flaws and the constraints of the major news media, and are at least looking for something else.

MAJ: I think they’re hungry for something else, because here’s the real deal: People who are young people, they don’t read newspapers, they don’t watch TV, because that media is alien to them. So, unfortunately, they might read news updates that someone has assembled, used media sources to assemble, but they don’t go to those original media sources, because they have no trust in those media sources. So they find out using other means.

But we’re, I think, on the cusp of creating citizen journalists, where, given the technology that now exists, everybody is a journalist. Because they have the potential to use their phones and broadcast to, really, uncounted numbers of people, to tell their stories and to get their word out, and to contact them and to give them insight into the world that they see, and not the world that the media want to project.

You remember George Floyd; it was a 17-year-old girl who was witnessing that, and when she livestreamed it, the world tuned in, and was transformed by that moment. So that’s just a taste of what journalism can do, when it’s at the right place at the right time.

JJ: And I thank you for that, and I think the corollary to the citizen journalism, and to people understanding that they can create their own news and witness and share, I think there is also an understanding that folks, when they’re watching the TV news, or they’re reading the paper, they also maybe are bringing more critical thinking to that, and recognizing that they don’t need to just swallow everything that’s in the New York Times. Am I being over-hopeful there?

MAJ: No, I think you’re absolutely correct. I think that’s part of that youthful vibration that turns kids off the newspaper or the local broadcast or even the national broadcast. I mean, I know quite a few young people who simply don’t watch TV. That’s an alien communications device to them.

JJ: Well, I could talk to you a lot, but I don’t want to take too much of your time. I want to ask you, certainly, before we close, to say anything that you want to say to a listenership of media critical folks. But I would ask—I read a quote from you recently that you said you’ve never felt alone. And I think that is gratifying, and probably surprising for people to hear, because many people, many people walking freely through the streets, are feeling very alone right now, really oppressively alone, for all kinds of reasons. And it might seem a weird question, but in September 2025, where are you finding hope? What are you looking to?

MAJ: I do find it in young people who are more open and more receptive, not just to stories, but to struggles. And I think that the gift of repression is that it wakes people up. I mean, people are seeing things that haven’t been seen in this country for years, and it’s waking people up. And so once you’re awake, it’s kind of hard to go back to sleep. And think about this: To the right wing, the worst thing you can be is woke. So that suggests that they want everybody to go to sleep. So wake up, be woke.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Mumia Abu-Jamal, author of many titles, including Writing on the Wall, Faith of Our Fathers, Murder Incorporated and 1995’s Live from Death Row, translated now into at least seven languages. Mumia Abu-Jamal, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

MAJ: Thank you, and thank CounterSpin. It has been a pleasure.

FAIR’s work is sustained by our generous contributors, who allow us to remain independent. Donate today to be a part of this important mission.

********

Janine Jackson

Janine Jackson is FAIR’s program director and producer/host of FAIR’s syndicated weekly radio show CounterSpin. She contributes frequently to FAIR’s newsletter Extra!, and co-edited The FAIR Reader: An Extra! Review of Press and Politics in the ’90s (Westview Press). She has appeared on ABC‘s Nightline and CNN Headline News, among other outlets, and has testified to the Senate Communications Subcommittee on budget reauthorization for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Her articles have appeared in various publications, including In These Times and the UAW’s Solidarity, and in books including Civil Rights Since 1787 (New York University Press) and Stop the Next War Now: Effective Responses to Violence and Terrorism (New World Library). Jackson is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence College and has an M.A. in sociology from the New School for Social Research.

What’s FAIR?

FAIR is the national progressive media watchdog group, challenging corporate media bias, spin and misinformation. We work to invigorate the First Amendment by advocating for greater diversity in the press and by scrutinizing media practices that marginalize public interest, minority and dissenting viewpoints. We expose neglected news stories and defend working journalists when they are muzzled. As a progressive group, we believe that structural reform is ultimately needed to break up the dominant media conglomerates, establish independent public broadcasting and promote strong non-profit sources of information.

*************

Contact:

Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting

124 W. 30th Street, Suite 201

New York, NY 10001

Tel: 212-633-6700

I was so happy to try to give him his journalistic flowers while he was here.

FEBRUARY 27th UPDATE: The Final Call’s tribute can be found here and here.

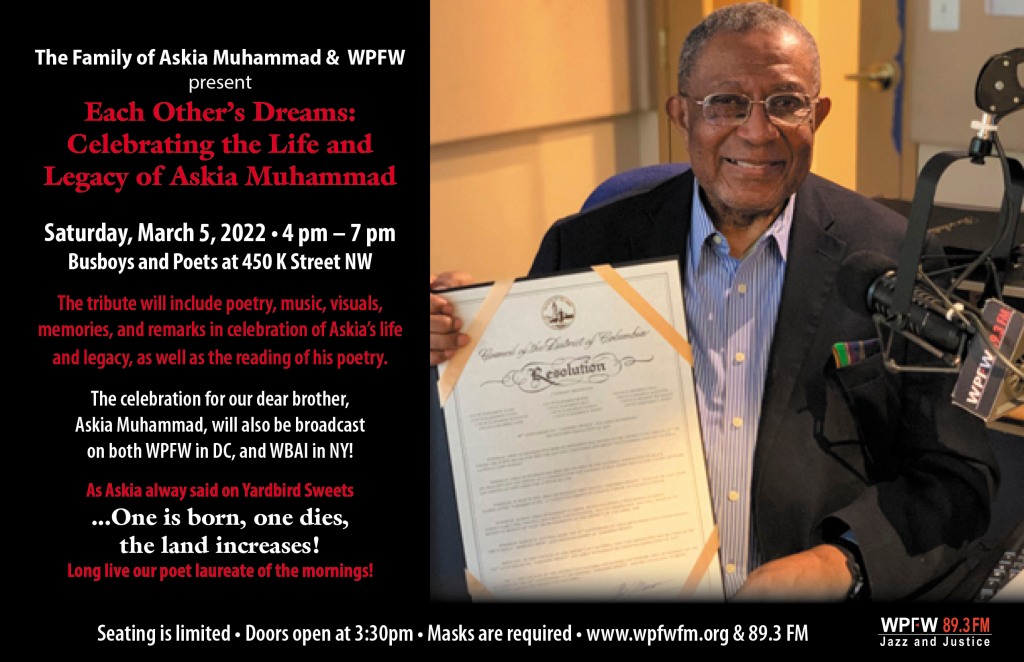

MARCH 5th UPDATE:

APRIL 2nd UPDATE: Coverage of the above event can be found here and here.

….is here!

……Juan Gonzalez, a journalist and historian who is ridiculously deserving of AT LEAST the Deadline Club’s New York Journalism Hall of Fame.

And Happy Early Birthday!

Leave it to Michael Eric Dyson to write this. (I remember he did something similar almost 20 years ago in his book “Race Rules.” )

It’s an interesting list. It would be a bit more interesting if it included people I met over the years, like Jared Ball and Rosa Clemente. They are no strangers to public intellectual work, but, alas, they don’t color within the lines.

But then again, looking at the older generation:

I just remember that Manning Marable and Earl Ofari Hutchinson were among those who started this “post-Civil Rights Movement Black public intellectual” thing 40 years ago on the Op-Ed pages of Black newspapers that only a few give a crap about now. Time is not the only thing that keeps on slipping into the future.

Enjoyed watching Eddie Conway’s interviews and comment on “Democracy Now!” this morning!