In celebration of Askia Muhammad’s new book, “The Autobiography of Charles 67X,” I wanted to present the following:

A few years back, I failed at an attempt to publish a book of my media columns. I wrote this essay, a tribute to Askia and those like him in the Black press, and asked him to respond.

The following is my unedited essay, from six years ago, and his response:

********

WHEN VOICES WERE BRIDGES TO DAYS OF FUTURE PAST

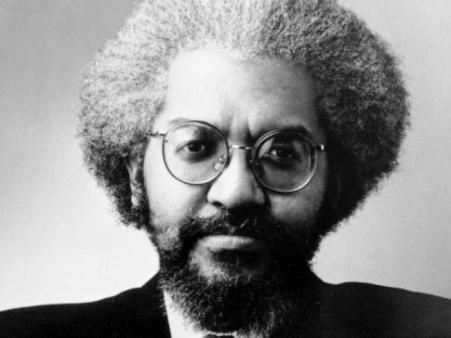

Me and the evening’s one-page program I’m scribbling on sat in the last row of the Black church, with me listening and looking around. Just sitting brought back memories. Sitting with the paper brought back more. The occasion was a March 2012 tribute to Askia Muhammad, Washington Informer columnist, 89.3 WPFW-FM/Pacifica broadcaster. Black nationalists, white leftists, and some big muckety-mucks in the Nation of Islam gathered under one roof for a celebration of a Race Man’s lifetime of writing and broadcasting, of observing and documenting. Journalist, columnist, and photojournalist. Poet. Commentator. NPR documentarian. Every Tuesday morning for almost four decades, he’s “Yardbird” playing (African-)America’s classical music, and every weekday evening he’s the host of WPFW’s “Spectrum Today” newsmagazine.

We—my body and its low-technological extension, the one-sheet program and pen, which collectively represent both my observations and my memories, now purged here—were in Reverend Hagler’s church, so my everyone’s favorite local Liberation Theologist should get the first word. “We don’t celebrate each other enough.” True dat, as I used to say when I was younger and actually looked like my old picture IDs. And Askia is still above ground! (I made the mistake of texting a veteran Black historian/journalist about the affair while waiting for the thing to start, and forgot to say the honoree was alive! Folks are sensitive to this kind of thing in 2012, because of so many thousands of formerly Youngbloods and Native Sons [and Daughters] gone.) So it’s all positive.

Somewhere in the church someone hit a trumpet solo. I saw The Man and his family. He was late for his own celebration because “Spectrum Today”—my vote for his greatest journalistic accomplishment—took precedence! His time-to-pull-out-the-good-china suit told me he left his ever-present bicycle home, for once.

Twenty years living in a metro area makes you understand its rhythms. At An Important Black Event in Washington, D.C., you have to see one of two folks—both, interestingly enough, from The Washington Informer, the city’s “other” Black newspaper. (D.C. has been an Afro-American town for nearly a century.) You will either see Askia Muhammad with recording equipment (or a pad, or a camera, or….), or you will see Roy Lewis, a.k.a. The Black Press’ News Photographer in D.C. If you see both at the same event, you know it’s the most important one of that day. I saw Roy before Askia came in, so I knew I was fine.

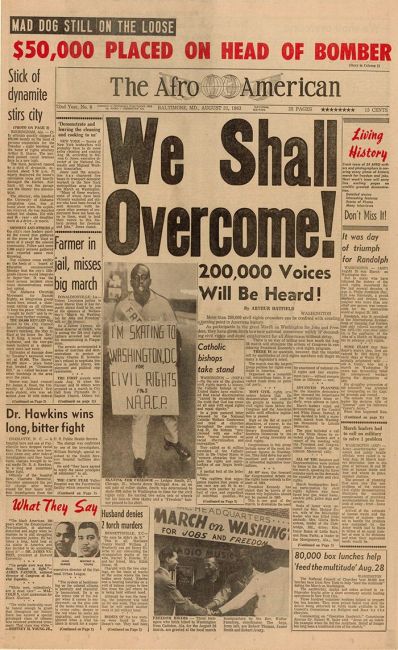

One member of the large leftist entourage postulated that those who have engaged in struggle for their entire lives “identify with Askia because he identifies with him.” Correct. Heaven forbid that a veteran of The Chicago Defender and a leading writer and editor for The Final Call doesn’t identify with those who wage what my favorite superhero shows call the never-ending battle. Call staffer Nisa Muhammad said Askia taught her how “to make each word count.” I started to remember things my sheet of paper couldn’t really record, like Robert Queen, the editor of The Afro-American’s New Jersey edition. Didn’t he used to do that for me? I remembered Deborah P. Smith, the kind, patient but direct woman who taught me journalism at Seton Hall University’s Upward Bound program in 1983 and started my professional journalism career in 1985 by telling Mr. Queen that I now was cubbing under her at The New Jersey Afro. I was 17, and was about to learn the same thing from Mr. Queen and Ms. Smith that Sister Nisa learned from Muhammad. And now, sitting there, in that church, I remember that Mr. Queen, who gave me my first press pass, is long gone. Along with so many others who, as Fred Rogers of PBS’s “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” told the 1997 Emmy audience honoring him for a lifetime of media work, “loved us into being.” So I, too, feel the identification. The sheet I’m writing on becomes useless, unable to properly contain the memories.

Always be careful of questions you ask, because you might have to deal with the answers. One Q-and-A created a permanent memory for me, guiding me to take history a little more seriously. My now-understood-to-be-dangerous question to Robert Queen was, “Do you think Black journalists today give you proper respect for your pioneering work in Black journalism?” His answer was, as they say on “Jeopardy,” in the form of a question: “If they knew, maybe, but who’s going to tell them?”

Fifty years in Black journalism, much of it at The Philadelphia and New Jersey Afros? Decades of commentary, a la “Bob Queen’s Review?” Who could forget that?

Turns out it was quite easy to forget all of it. A “segregated” mass press created to serve segregated communities in the early days of the last century. Newspapers that were sold in the corner of bodegas in the communities, later ghettoes, of America. “Ethnic media,” the white folks who define American journalism for all Americans kept calling it. Older Black folks read those old Black weeklies Queen worked for—The New Jersey Guardian, The New Jersey Herald News, The Philadelphia Independent, The Pittsburgh Courier, and those two Afros. Older folks who became Ancestors in the last 20 years, like Mr. Queen did in October 1996 at 84. And with the exception of The Courier, all those papers now “exist” only on microfilm somewhere in libraries in New Jersey and Philadelphia, hopefully. After all, if something doesn’t have an active, present (read: online) archive in 2012, it never existed at all. It only lives as a sentence in a Wikipedia entry, if it’s lucky.

I always remembered that 1989 interview with Mr. Queen, who, in my mind, was my journalistic “granddad.” That question. Thinking about an answer put me, 22 years later, with diplomas from the University of Maryland at College Park and, ultimately, with a job at Morgan State University and, in a way, in that D.C. church right now, making sure I saw Askia Muhammad, a man trained by Queen’s generation of Black press journalists, getting his proper due. The tribute was proof of his existence then and now, his life already lived and the deadlines to come. The fact that the video and audio and photos taken of the event is today’s proof as well as tomorrow’s history was important for this Black press historian to think about. Someone will tell them, whoever “someone” and “they” will be, about Askia Muhammad—assuming radio doesn’t go the way of Blockbuster and FYE, admittedly a big assumption.

Some new memories, not surprisingly, become simultaneously connected to old ones. So many things have now been written about a relatively new Ancestor, a Black scholar by the name of Manning Marable. (I should know; I co-edited a book, and contributed to a second book, blasting Marable for his failure to produce a solid biography of Malcolm X.) Most have mentioned, but not focused, on his journalistic work as a columnist. Marable became a Black press columnist in the late 1970s, around the time Askia was breaking into WPFW.

Manning Marable, like most of us, had a beginning. Robert Queen had been a newspaperman for at least two decades and was just settling into his final stint at The New Jersey Afro-American by the time the teenage Marable of Dayton, Ohio, caught the Black newsprint bug at The Dayton Express. His column was called “Youth Speaks Out.”

He attempted to live the life of a young writer. He covered the funeral of Dr. King. During and after earning his Ph.D. in the mid-to-late 1970s, he became a Black press columnist. He decided to self-syndicate a column, called “From The Grassroots,” which eventually became “Along The Color Line” during the Reagan years.

Marable was part of what could be called the Third Generation of Black press columnists. The first generation was filled with 19th century luminaries such as Samuel E. Cornish, John Brown Russwurm, David Walker, Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells. The second contained the giants of the pre-Martin Luther King/Malcolm X segregated era like Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson, George Schuyler, and W.E.B Du Bois. Marable and others of his generation—Tony Brown (of PBS’s “Tony Brown’s Journal”), Charles E. Cobb of the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice, National Urban League head Vernon Jordan, and Marian Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund—claimed the Black press during its long and slow decline. America had not only desegregated, it had begun to replace print with broadcast. In the case of Black America, that meant that the relatively new kids on the block, local and national Black public affairs television (like Brown’s show) and “soul”-formatted FM radio was crowding Black traditional media’s space. So Black press commentary went from leading Black America one opinion at a time to just being part of its collective DNA.

The column’s distribution grew, and while it did he discovered his voice and its language for his ideological and political development. He wrote that his column was the “anchor” he created to find out where he found himself ideologically. The professor found himself a small-but-influential chronicler of a new era created buy the spilling of King and Malcolm’s blood. Harold Washington, Benjamin Chavis and Louis Farrakhan became subjects or targets of his critical acumen. But his best factual venom was saved for Ronald Reagan. Marable melded current events and history in an attempt to create a collective print memory, one that could be passed around and referred to for as long as the page didn’t tear. In the 1980s, Marable had a young reader who discovered him while he was writing for The New Jersey Afro-American. That young Marable reader would join him on national Black press Op-Ed pages for most of the 1990s. It’s all connecting now. The paper and pen are put away.

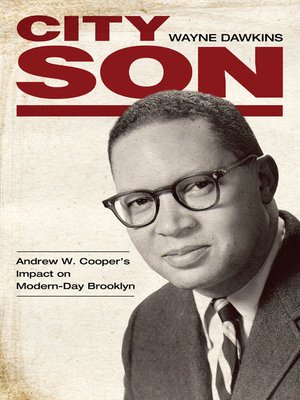

Around the time Manning Marable was starting his self-syndication, a slightly younger Black man from Brooklyn by the name of Wayne Dawkins was practicing his journalistic craft in the Black press by working for another Black man by the name of Andrew Cooper and a Black woman named Utrice Leid. Cooper, a traditional Race Man, died in 2002. After three decades of journalism and book publishing (as author and self-publisher), Dawkins, a post-modern Race Man, came full circle when wrote City Son, a 2012 book about Cooper’s life, the Black press wire service he and Leid created, the Trans-Urban News Service, and their subsequent newspaper, that Brooklyn dive-bomber, The City Sun.

Cooper had a column, “One Man’s Opinion,” in The New York Amsterdam News, but his coffee burned too many laps. So he and Utrice Leid ran a wire service. But they wanted, and their community needed, more. So they started a newspaper so editorially fierce it was one of—if not the only—Black newspaper in America to openly not endorse Jesse Jackson for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988, and had to guts to say that it was because he had sold out the Black community. It was so journalistically fierce New York City Mayor Ed Koch, the arch-enemy of Black New Yorkers, always had Cooper’s phone number nearby, to call and complain. Cooper and Leid loved The People and the fight, and taught others to do so, too.

Dawkins’ book does what all good books do—connects Cooper’s/Dawkins’/Black journalism’s/our past to the present, from the far away days of the 1960s to the still-days of Askia Muhammad. Until someone writes about them extensively, doing what Dawkins’ did to/for Cooper, Queen and Marable, in contrast, will just be seen as Ancestors, having finished fulfilling their roles of using media to morph yesterdays into todays and back again. But they will stay in their own yesterdays. First in print, then in microfilm, and now on databases, their ideas are neatly filed away awaiting discovery, like old pennies under the mind’s collective couch cushions. As people, they still live in the memories of people who remember them. We honor their memories because they—the people and the ideas—are part of our collective consciousness. They are part of our reflection on the days we choose to see and know ourselves.

For more than 30 years, Askia Muhammad has cycled in to WPFW to recycle these collective memories in a vain attempt to make them self-sustaining. He makes them momentarily float in the air. On a good day, they enter the minds of those who, in their day-to-day lives, are struggling to remember that they didn’t always belong just to themselves. He fights for the poem to outlive the poet and his telling. Like Marable, Queen, Dawkins, Cooper and hundreds of others over the centuries, Future Ancestor Muhammad writes for the same reason many of us do: to be part of the world concert filled with every writer who has ever lived, to try to make his small instrument heard within the eternal jam session. He is needed by them/us, so they/we honored him for creating a reliable, steady one-man band-cum-brand of consciousness, news and infotainment for so many decades. And so Ancestors who were scribes who we did need once upon a time, and who Muhammad represents by his very acts, await to be resurrected again, await someone to call out their names, and thereby recycling their consciousness into the iPad age.

But what happens when all those Twentieth Century djelis (griots) who have been remembering for so long, who have been consistently transmitting for so long, join the remembered in the Realm of the Ancestors as the new century, the new millennium, continues? That’s my dangerous question. Someone is about to hit a trumpet solo, so we are about to find out.

June/July 2012

********

ASKIA-AT-LARGE–10-1-12

Response for Todd Burroughsby Askia Muhammad

In the summer of 1968, less than two months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I was one of 12 Black interns at Newsweek. Coincidentally, all of Newsweek’s interns that summer were Black. Thanks to writer Johnnie Scott, a high-school buddy, and Newsweek writer Nolan Davis, I was employed in Los Angeles where I grew up, with Bureau Chief Karl Fleming and correspondent Martin Kassindorf.

Born in the Mississippi Delta 23 years earlier, I knew when I was picking in High Cotton, and this was High Cotton.

I resigned from the U.S. Naval Reserve Officer Candidate Program in order to accept the Newsweek internship. I spent the previous summer at Officer Candidate School in Newport, RI.

But in 1968, everything was beginning to look very different to me. Despite the passage of landmark Civil Rights legislation, racial unrest remained at an all-time high, and I was affected by it. There were riots increasing all over the country, even before Memphis in April. Racial resentment blended in me with increasing opposition to the Vietnam War.

I found myself at the first crossroads of my career. I decided that my chance-of-a-lifetime internship at Newsweek meant more to me than becoming a U.S. Naval officer during an unjust war. “The Viet Cong never called me a nigger” I learned from heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali.

Coincidentally, at the convention of the National Association of Black Journalists in Los Angeles in 2000, I managed to inquire of one of Newsweek’s corporate-suits-in-attendance about the persistent rumor I had been hearing that the magazine had no Black interns that year or the year before, or the year before that. I never got a conclusive denial; neither could I get a confirmation of my suspicion.

But the lesson to be learned from Y2K Summer Intern Apartheid, is the same one we see in Y2K-plus Sunday Morning Apartheid. Face it; we’re living in a different reality today. There is no blood spilling in the streets. There is absolutely no collective White guilt remaining in the society. In point of fact open contempt for Black folks is expressed every hour on the hour in 2012 America. On the eve of Election Day and beyond, the lower-downs of White society beat the President of the United States like he’s a rented mule. And from the higher ups it’s as though the rest of us aren’t even living on the same planet with them. There is just no pressure today to guarantee media job opportunities for Black folks anywhere, whether it’s as summer interns, or as guests or panelists on Sunday morning news shows.

Now, I’m honest enough to confess that I’m just another middle-aged hack, in the twilight of a mediocre career. But I also realize thanks to Newsweek, I reached a lofty plateau practicing journalism–mostly in the Black Press, the non-corporate-owned press. It was the best possible thing I could have done with my life. For the last 40-some-odd years I have been writing a contemporaneous account of late 20th Century and early 21st Century history. And in my world, most of the prominent heroes and sheroes all happen to be descendants of slaves like me.

At the same time, I had the best of both worlds. Like Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, I am conflicted: “an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.” I am an endangered species, a heterosexual Black man in a White, Holly-weird-dominated news media. But like Brother Malcolm X, my relative anonymity in the Black Press left me free from having to be concerned on a daily basis, with whether or not White people liked what I had to say. And furthermore, I got a glimpse at how that “other half” lives.

Thanks that is, to a decision I made at the end of my Newsweek internship, although I did not know its significance at the time.

During my 12 weeks working in an office in a swank building on Wilshire Boulevard in L.A., I very rarely lived beneath my privilege. I experienced the power of working at one of the media’s then all-powerful “Seven Sisters:” ABC, CBS, NBC, Newsweek, Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post. Corporate executives, defense contractors, movers and shakers, returned my phone calls. I got nice gifts, free tickets. I met Bill Cosby in private. I met Jose Feliciano. This was High Cotton I was picking in, and I knew it. Today, while there are many more elite media platforms available, there are still precious few opportunities for Blacks, unless for the most part they are willing to “coon” or to simply betray the best interests of their people.

But back in my 1968 real life there was a world of radical and racial identity politics awaiting me. There was the Black Student Union at San Jose State. There was The Son of Jabberwock, the off-campus “underground” newspaper I was blessed to publish there.

One day I was thinking about why I wasn’t more delirious at being in the “big time” at Newsweek. I realized that if I got a permanent job at NW my identity would be represented by my name printed in a slug of agate-sized type–C.K. Moreland Jr.–indistinguishable from all the other slugs of type in the magazine’s weekly masthead. But I wanted my name to shout that I was a Brother, so that other Black folks would know that the doors were now opening and that I had found my way inside and was doing fine.

Toward the end of the summer the magazine’s editors helped me resolve my dilemma. A query was sent to all bureaus: the editors wanted to know if Black folks had given to naming their children after Civil Rights heroes and which ones? The L.A. assignment came to me.

I called hospitals. I called birth certificate offices. What I discovered was that Black families were giving their children African names, Muslim names: “free names,” instead of “slave names.” I interviewed Los Angeles Black Nationalist intellectual, Dr. Maulana Karenga, the originator of the Kwanzaa holiday.

What did I go and do that for? I got a rebuke from Hal Bruno, then Newsweek’s Chief of Correspondents, for not having correctly reported the assignment I was given. I defended myself believing that I had–without any racial agenda of my own–done the honest street reporting which led me to the conclusions that were included in the piece that I filed.

Newsweek and I parted friends at the end of the summer. Karl Fleming even wrote a nice job reference letter for me later, but when that internship ended, I knew that I would probably never be happy working at a place where my world view and any facts I might report notwithstanding, would always be subject to some higher verification according to the prevailing White cultural prism.

Later that year, after I skipped a Navy Reserve meeting to attend a Black Power conference at Howard University at the invitation of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) leader Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure), I joined the Nation of Islam and I became a conscientious objector.

In the summer of 1972 I was called to Chicago by none other than the Honorable Elijah Muhammad himself, where I became Charles 67X, and eventually Editor-in-Chief of Muhammad Speaks newspaper, succeeding a Hall of Fame list of previous editors, literary lions all: Dan Burley, Richard Durham, John Woodford, and Leon Forrest.

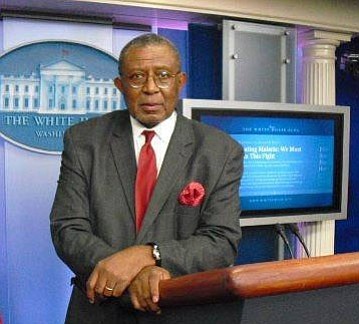

In 1976—by then known as Askia Muhammad—I went to work for The Chicago Defender, and following the election of Jimmy Carter to the presidency that year, I was sent to revive the Defender’s Washington Bureau where the legendary Ethel Payne had served.

“History is best qualified to reward our research,” I learned from Mr. Muhammad, and here in Washington, with the likes of Thurgood Marshall at the Supreme Court, Shirley Chisholm in Congress, and Patricia Roberts Harris, and Ambassador Andrew Young in the President’s Cabinet, I continued to witness history unfolding right before my eyes, only now on an international stage.

In 1968 my reaction at Newsweek was simple and arbitrary. In the 44 years since, I am convinced that the stories I first reported, from my race-conscious perspective, were valid, even visionary. As Brother Charles 20X, West Coast Correspondent for Muhammad Speaks newspaper from 1969 through 1972, I interviewed Mrs. Georgia Jackson and Jonathan Jackson, the mother and brother of legendary Soledad Penitentiary inmate George Jackson. I covered the funerals of both Jonathan and George. I reported the Angela Davis trial held in San Jose. I even occasionally took Bean Pies to the jailhouse for Angela and for her attorney Howard Moore.

This process helped me become a more caring reporter. I think I “got something” during this training period, which continues to shape my choices. Charles Garry was a famous San Francisco Bay Area attorney I interviewed. He defended Black militant clients, among others. He told me a lesson he learned during his apprenticeship. Perhaps he had been a clerk for Chief Justice Earl Warren. I don’t remember precisely who it was he said taught him the motto: “if I make an error, I hope I always err on the side of mercy.” That became my new motto.

So I’ve always understood the claim of innocence made by Ruchell Magee, the jailhouse lawyer who was in the Marin County Courtroom on August 7, 1970 to testify on behalf of another inmate when Jonathan Jackson stood up, brandished weapons and took over the courtroom, kidnapping the judge, two prosecutors, and three jurors as hostages. Magee, not a part of the jailbreak plan, decided spontaneously to join.

All totaled now, he has spent nearly 50 years in California prisons for what were originally petty crimes, petty, petty crimes, aggravated however by his persistent complaints that he remains unjustly imprisoned. I’ve always understood what caused him to decide his chances were better, attempting to break out of that jail, than remain in the clutches of people who had consistently denied him justice and a fair hearing.

In the same way I understand the appeal from Mumia Abu Jamal, that he remains unjustly imprisoned. I believe he’s innocent. I met and interviewed Mumia once in Pennsylvania SCI Huntingdon. His hands and his feet were shackled to his waist. A wall of thick, bullet-proof glass separated us. I believe he was improperly convicted of killing a police officer. And I applaud his caustic condemnations of the injustices that George and he and Ruchell endured and continue to endure in the hands of the American Just Us System.

I understand the plea of Wayne Williams, who has always maintained his innocence. I spent a month in Atlanta in 1981 during the series of child murders there, producing a documentary for Pacifica Radio station WPFW-FM in Washington: “Atlanta, How Much Can We Stand, Day 600?” I reported and continue to believe the murder of those Black children in Atlanta was a racist plot.

During my career flying well below the radar of media super-stardom, I know myself to have been blessed and highly favored. Over a period of 25 years I did dozens of commentaries for NPR’s “All Things Considered.” I have produced 10 documentaries for the public radio series “Soundprint.” Todd Burroughs calls those documentaries my “Autobiography via Soundprint.” Some of that radio work has won multiple national awards.

I’ve written a half-dozen or more op-ed articles for The Washington Post, my articles have also appeared in The Chicago Tribune, The Los Angeles Times, The Baltimore Sun, USA Today, Jet, and Downbeat, and since 1992 I have been a proud columnist for The Washington Informer, since 1996 I have been a feature writer for The Final Call, and since 1979 I have been host of the Tuesday morning drive-time Jazz program at WPFW-FM in Washington, where I’ve been employed intermittently during that time as News Director as well. As my friend Dan Scanlon of Mutual Radio reminded me once: “Not bad for a middle aged hack in the twilight of a mediocre career.”

Blessed. That’s like slaves picking in High Cotton.

Today I can truthfully say that I’m not stuck ideologically back in the 1960s. I’m not nostalgically trying to bring back a lost militant movement. No. I’m just a warm up act for our powerful storytellers who will take us the rest of the way through the 21st Century.

That’s the way I see it. I think that’s the way it is.

–30-30-30–

Pingback: Askia Muhammad Dies, Multimedia Race Man – journal-isms.com

Pingback: Asante Sana, Askia Muhammad | Drums in the Global Village