DECEMBER 24th UPDATE:

Tag Archives: Harlem

PRESS RELEASE: He Was A Black Power Icon On “Sesame Street.” Then He Was Evicted. A New, Free Online Novel On Medium.com Tells The Full Story Of America’s First Black Muppet.

February 1, 2024

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT: Todd Steven Burroughs (toddpanther@gmail.com/@ToddStevenBurr1)

NEW, FREE ONLINE NOVEL ON MEDIUM.COM TELLS THE STORY OF HOW AMERICA’S FIRST BLACK MUPPET, A SYMBOL OF THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT, WAS EVICTED FROM “SESAME STREET”

A PEOPLE’S NOVEL: At The Dark End of Sesame Street: The Autobiography of Roosevelt Franklin

(OR

Coup Tube: The Prose Ballad of Roosevelt Franklin)

Roosevelt Franklin, one of the first breakout stars of Sesame Street, has been called “The Black Elmo” but he’s really a Black Power pioneer. It’s why author Todd Steven Burroughs decided to take the plunge and further fictionalize the life of a network TV puppet.

“The more I read about Roosevelt, the more I realize that a puppet actually went through the Black Power experience,” said Burroughs, who, at 56, was part of the first generation of American toddlers to watch the then-brand-new “Sesame Street” on PBS. So it was clear to him that Roosevelt’s “life” had to be explored in-depth.

“Originally I was going to write an article, but that had been done to death already,” said Burroughs, a freelance writer and public historian. “I was going to make it a little different by doing one of those long magazine pieces that would have allowed Roosevelt his first-person segment—a mini-platform to tell his own story—and that idea expanded into this attempt at fan fiction.”

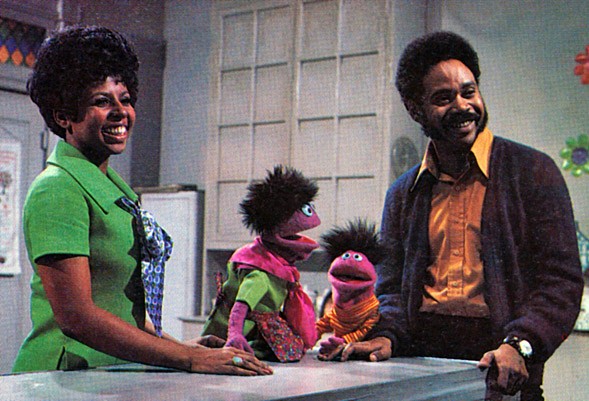

Roosevelt Franklin was created by Matt Robinson, the show’s first “Gordon” (pictured, along with Loretta Long, still the show’s “Susan” in 2024). Decades before “Elmo’s World,” he was the first character to get his own “Sesame Street” segment named after him, “Roosevelt Franklin Elementary School,” a series of skits that had Franklin work as a student teacher at a vibrant, noisy, inner-city school.

Another pioneering power-move: he was the first Sesame Street character to get an album. It was released in 1971 and re-released in 1974.

A mainstay from 1970, the year after Sesame Street began, to 1975, he was even one of the show’s first toys.

So what happened?

“Roosevelt was a victim, ultimately, of middle-class Black respectability politics,” said Burroughs. “Once I saw his arc and how it intersected, and even mirrored, the Black Power Movement and the problems and paradoxes of racial integration and cultural nationalism, I knew I had to do something a little different, to tell the story I began to see in my own mind—basically write the last Black Power memoir about someone who, pun intended, wasn’t going to be The Man’s puppet.”

Published in full and for free on Medium.com, At The Dark End of Sesame Street fills in significant gaps in Roosevelt’s story, giving him friends and mentors—some of whom are very well-known in New York’s Black communities in the early 1970s—and, by doing that, tells fun and interesting tales about television, music, and finding a sense of purpose. Along the way, it exposes the internal tensions that are inevitable when a young Black man tries to balance the demands of white liberalism and Black radicalism during the Black Power era.

“The weirdest part for me was writing a story that mentioned both pioneering New York Congresswoman Shirley Chisolm and Big Bird,” said Burroughs, a lifetime student of New York’s Black public affairs television programming and Black radio history. “TV has always created strange bedfellows, and this novel is no different.”

############

DISCLAIMER: A PEOPLE’S NOVEL: At The Dark End of Sesame Street: The Autobiography of Roosevelt Franklin (OR Coup Tube: The Prose Ballad of Roosevelt Franklin) is a nonprofit work of fanfiction written and posted for free online consumption, and hopefully enjoyment, under Fair Use. Roosevelt Franklin is a fantasy puppet character created by a real Black man, Matt Robinson, for use by the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW), now known as the Sesame Workshop. Sesame Street is a creation of the Children’s Television Workshop for the Public Broadcasting Service and HBO and is trademarked by Sesame Workshop. The Muppets were created by Jim Henson and the CTW. All Sesame Street Muppet characters are trademarked and copyrighted by the Sesame Workshop. All images, names and likenesses of Sesame Street characters, puppets and PBS actors used in this promotional material and in the novel are done under Fair Use. No copyright nor trademark infringement is intended.

Book Micro-Review: Alone, Together

Claude McKay: The Making of a Black Bolshevik.

Columbia University Press, 464 pp., $32.

In the first of an apparent two-volume work, James demystifies the iconoclastic McKay by immersing him in the colorism, colonialism and capitalism of his native Jamaica. Because his upbringing is so intellectually, culturally and personally fierce, to be fully awake is a choice that would have been difficult for him not to make, even though many around him actively preferred the blissfulness of social slumber. A wide-eyed search for the perfect space leads to intellectual daydreams of a far-away land filled with hammers and sickles, items that would become the ideological tools of many, many 20th-century Caribbean, African and Black radicals. The origin story of a poet who, regardless of the racial and classist fires all around him on both sides of the Atlantic, refused to stay in an inglorious spot.

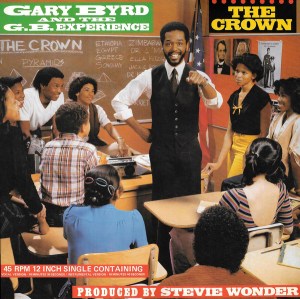

An Origin Story of Gary Byrd, From “Disc Journalist” to “World African Griot”

Gary Byrd turns 70 tomorrow. I thought this was as good an excuse as any to pull this out of my 2001 doctoral dissertation–an attempt to define Black (American) media ideology–to say an early “Happy Birthday.” Any mistakes are mine, and I welcome corrections from Byrd and all others. Happy Birthday, Brother Byrd!

A Byrd Flies In Buffalo

A major portion of the story of Black media can be told through the life and career of Gary Byrd. The radio veteran, who in the year 2000 was in his early 50s, is considered one of the links between the pioneer Black broadcasters and the current generation. Byrd’s 30-year career in broadcasting in New York City and Buffalo displays all facets of how Black media function.

Byrd began his radio career as a teenager in Buffalo, N.Y. Hearing Byrd’s powerful, charismatic speaking voice in a 1965 high school play, a part-time disk jockey for WUFO asked the fifteen-year-old if he had thought about a radio career. Byrd joined WUFO and, by the time he was 17, set his sights on WWRL. He was initially offered a job, but his grandmother made him turn it down until he finished high school. After a brief period at WYSL, located in upstate New York, Byrd joined WWRL in 1969 at the age of 19. His tenure there gave him the freedom to experiment that would allow the young disk jockey and poet to grow spiritually, intellectually and journalistically on the air.

“The Gary Byrd Experience”

In 1970, Byrd was given WWRL’s all-night spot. “It was late at night at the station … [the management said,] ‘Do what you can to keep the people up.’ They left me alone.” Being left alone to test ideas on the air during a time of experimentation in FM radio, the Black Power Movement and the Black Arts Movement, Byrd developed “The Gary Byrd Experience,” a blended and layered mix of music, interviews, radio news footage and his own Gil Scott-Heron-like poetry. (This format was similar to the one Del Shields used on his “Total Black Experience in Sound” show on WLIB-FM–a station that would, in 1972, be renamed WBLS-FM–but Byrd identifies his influences then as social comedian Dick Gregory and message-oriented soul music of the late 1960s. The program’s name is Byrd’s take on rock legend Jimi Hendrix’s band, “The Jimi Hendrix Experience.”) One of the poems Byrd created that he used on the air in the early 1970s was “Every Brother Ain’t a Brother,” his 1969 commentary on the social forces surrounding the Black Power movement. He said he wrote the poem because “at that time there were some interesting contradictions in the Black community.”

It‘s time for us to face the truth and level with each other

It‘s time for us to face the fact that every brother ain‘t a brother.

There are some who‘ll say to the world at large

I’m no color. I’m just a man.”

And some say to the folks uptown that Black Power is not their plan.

But through it all we fool ourselves and fool one another

By failing to face the simple fact that every brother ain’t a brother.

Now there is a kind of brother who shoots a brother and thinks that makes him bad

There‘s a kind of brother who says he’s Black because now it’s just a fad

We‘re at the point in the world today for self-evaluation

Just to find out where we really are in this racially tom-up nation

And one of the first things we must do is stop kidding one another

And get on the case of realism that every brother ain‘t a brother.

Now I said that every brother ain’t a brother

And I know you know that’s true.

But look in the mirror carefully

‘Cause that brother might be you.

Byrd began to redefine the role of disc jockey, calling himself a “disc journalist.”

His use of issues and music brought him attention from a fan of his radio show, musician Stevie Wonder, who invited him to write the lyrics to two songs, “Village Ghetto Land” and “Black Man” on Wonder’s double-album classic “Songs In The Key of Life.” In addition, Byrd recorded his own albums of poetry. With Bob Law, who became WWRL’s program director in the 1970s, Byrd attempted to bring the concept of predominately white “progressive FM” format to AM radio, but in a way tailored specifically to the needs of New York’s Black community. In 1984, Byrd would make a career move that would expand his reach and influence, and ultimately find a sphere of thought that he could claim as his own and share with his audience.

A Byrd Takes Flight As A New Experience Begins

By 1984, three years after Law’s “Night Talk,” a nationally syndicated Black talk radio program, debuted on WWRL, new talkers were on the WLIB airwaves. Mark Riley became WLIB’s mid-morning host, after the morning newscast. Gary Byrd became the early-to-late afternoon host on the daytime AM radio station. “The Gary Byrd Experience” had evolved from Black music to Black talk, and Byrd began to mix music to set the mood for his interviews and discussions. WLIB had a broadcaster in Byrd who attempted to meld the spiritual (music) with the social-political (talk) aspects of the African-American experience.

‘The Gary Byrd Experience” on WLIB, in Byrd’s mind a radio magazine, established Black rituals of sound. Each of the opening segments had its own particular sound, blending jazz with gospel, with Byrd’s voice opening and closing the show over the music. Unlike Riley’s show, which was call-in talk interrupted by music cues, Byrd, with music, rhyme and tone, tried to create a cultural atmosphere with his predominately Black audience. His “question of the day” for the audience, the focus of the leading segment of his program, was a more philosophical one than poised on the more news-oriented Riley’s show. When I began listening to him in 1987, Byrd referred to himself a “New Age Griot,” the latter French term referring to a name given to male West African praise singers who sing the history of a particular person, family or community.

A New Name, A New “GBE,” A New Site

While living and working in New York City in the 1970s and early 1980s, Byrd, who read on his own about Africa, began to be exposed to African-centered scholars such as John Henrik Clarke and Dr. Yosef ben-Jochannan (known as “Dr. Ben”), who often delivered public lectures to cultural Nationalist groups and others. Jochannan, an Egyptologist, taught that the ancient Egyptians who shaped human civilization were Black-skinned Africans. Byrd told Gil Noble during a 1999 WABC-TV “Like It Is” interview that he was prepared “to sit at Dr. Ben’s feet” when he heard a tape of a speech of Dr. Ben’s. In the mid-l980s, Byrd went to Egypt, where he was told by a priest to go to a certain place along the Nile River and perform a ritual to gain a spiritual experience. That ritual, he recalls, gave him the inspiration to give himself a name that “would give me something to aspire to every day of my life, a new place to step to.” He adopted the name Imhotep, the legendary Egyptian first multi-genius.

Byrd began using his new name publicly around 1990. It was shortly after he did a special week of programming from the Apollo Theatre honoring African-centered scholars such as Clarke and ben-Jochannan. As a result of the success of those broadcasts, Byrd was given the mid-morning slot, live from the Apollo. With this move in place, Byrd subsequently announced that his name was now Imhotep Gary Byrd and that he was re-christening his show the “Global Black Experience.” The broadcaster, dropping the “New Age” from his self-description, had now decided to become the African-American broadcast equivalent of an African griot–a living medium for African-Americans, with the mission to “make African people feel good about themselves, and to make the world feel good about African people.”

The “New GBE: Africentricity,” as he called it, was done on the Apollo stage, a center of Black American culture. Still essentially call-in talk radio, it was done with a live studio audience, who came in from the street to see the show. Guests were onstage talking with Byrd–wearing dreadlocks and dressed in flowing African robes–while the members of the studio audience lined up to ask questions or to win prizes in a Black history quiz question Byrd would ask on-air.

The show became politically and culturally stronger in tone-as strong to the Black Cultural Nationalist left as white mainstream talk show radio hosts Bob Grant and Rush Limbaugh of WABC-AM were to the white right in the 1980s and 1990s. The new “rituals of sound” were more African and less African-American. The “new” GBE began with a recorded call to “Speak, Drums! Tell the real story.” After the theme, Byrd would read aloud the Nguzo Saba–the seven principles of Kawaida theory developed by Black Cultural Nationalist Maulana Karenga and popularized by the Karenga-inspired African-American holiday, Kwanzaa–at the start of every show. These principles include calls to African unity, self-determination and purpose. Then Byrd would read the headlines from The Daily Challenge, the city’s only Black daily newspaper. On “Black Press Thursday,” the day most of the city’s weekly Black newspapers would be on the newsstands. He read headlines from all of the city’s Black press. Byrd took advantage of the use of a well-known stage and culturally-eager studio audience to honor people who had made significant contributions to African and African-American life.

The significance of the “New GBE,” from a cultural standpoint, cannot be overemphasized. Byrd, by 1990 a cultural hero of sorts and opinion leader in New York’s cultural Nationalist and activist communities, was now broadcasting an African-centered show from the Apollo Theatre, a legendary Harlem landmark on 125th Street–the same street used by many of the streetcorner orators, including Malcolm X. These ancestors now had descendants with new, more sophisticated stepladders and megaphones. The unedited voices of these “children” could now be heard around the nation’s No. 1 local media market–the New York tri-state area–in cars, homes, or on Walkmans while jogging. Black senior citizens and others who learned about Black history and culture from Byrd and his guests could now drop by to see them in person and ask questions. Teachers set up class field trips, as I helped to do in 1992 for journalism and broadcasting high school students attending the Seton Hall University Upward Bound program. “The New Negro Movement” of the 1930s had become a 1990s African-centered renaissance, live, on-air. The “New GBE” allowed Blacks to participate in a collective African-centered media experience, using the most powerful medium in Black communities, the radio.

My New Book Review, About A New Collection of Elombe Brath’s Writings,……….

My Day At The Movies: “I Am Not Your Negro” And “Chapter And Verse”

I celebrated my birthday six days early by going to the movies. Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro” and Jamal Joseph’s “Chapter and Verse” were on the Black indie bill.

Peck is my kind of Black artist. All I really know about him is that he made “Sometimes in April,” “Lumumba” and now this. For me, that’s enough. The Haitian filmmaker used the access he got from James Baldwin’s estate well: he was able to use the outline of one of the writer’s unfinished works, “Remember This House.” Using that piece was an interesting choice, because it meant that the film was not about Baldwin, but about that outline’s subjects: Medgar, Martin and Malcolm. Peck takes that outline and Baldwin’s many recorded interviews and speeches as a base and, with the help of narrator Samuel L. Jackson, seamlessly expands into the essayist’s seemingly entire body of work. America and its mythologies are explained in ways that, yes, cliché though it sounds, are still relevant today. (His and Peck’s quick, time-travel dismissal [sort of] of the Obama years was amazingly well-done; in 40 years, Baldwin scoffs, mocking Bobby Kennedy, “if you’re good, you can be president.” And the Obamas flashed on the screen, symbolic of the instant they occupied, before the film returns to the struggle.) Peck, in full control of his “missing” Baldwin (audio)book, shuttles back-and-forth in time so smoothly that, for an instant, the viewer is confused which period she inhabits; a black-and-white Trayvon Martin fits well into the historic flow. For a writer who used the words “frightening” and “terrified” so much, Baldwin was actually quite fearless. He could say that whites acted like monsters, like he does here, and somehow can get away with that. I miss that level of courage in Black people today. Peck, who succeeds in salvaging and presenting that heroism, pushing it into the Trump Era, has the kind of intellectual clarity that Baldwin would appreciate.

I guess Joseph would wince and give me the side-eye if I said “Chapter and Verse” was (just) “Boyz ‘n’ the Hood” for the millennial generation, starring a new-jack Socrates Fortlow. But that’s what it is, and there is nothing wrong with that. Joseph wants the entire Black community to be his audience, so he has something for everyone: for youngsters who crave ‘Hood violence, check; older people who will identify with Loretta Devine, who anchors this film, check; images of historic Black leaders in the background (are they sad angels, witnessing the 21st century Black dysfunction?) for the “conscious” filmgoer who knows he’s watching a film about Harlem done by a Black Panther, check. It’s the sum of its parts, no more and no less. And that’s far from a crime. It’s ambitious only in its theme that the survival of the many takes real planning and real sacrifice by the few.