A little too gentle a parody, but enjoyed the Dame Maggie Smith imitator! LOL!

Category Archives: television

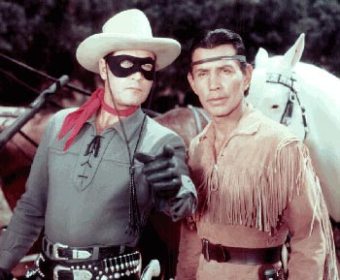

Why Didn’t Tonto Just Kill The Lone Ranger?

I have to confess that I’ve watched a lot of “The Lone Ranger” in the last month or so, including and especially the two original-cast movies. To justify this, I keep thinking of why Tonto is so helpful. Is it because he gets to beat up white people? Is it because, in my mind, he kills the Lone Ranger in the end when he realizes the white-eyes will take all his people’s land? Would he like that in the 21st century a white boy who is using the one-drop rule to an extreme will be playing him this year? Tonto speaks to me, but not in broken English.

Publicity Hound? (Sorry, I Couldn’t Resist :))

Of course, the superhero-rescues-animal gold standard is still saving a cat stuck in a tree… 🙂

“Cheers” Moves To Ireland?

Great idea! Boy, I miss the days watching “Cheers” and “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” 🙂

Would You Know My Name/If I Saw You In Heaven?

For Jamie Foxx :)

Boy, is Jamie in the news lately! LOL!

And now, this “gaffe” concerning this film 🙂 (Y’know, in Washington, D.C., folks say a “gaffe” is when you catch a politician saying what he really thinks. :))

And the introduction by NoNSanDiego is HILARIOUS!!!! 🙂

Fighting For Morgan

To go forward requires the commitment to move in that direction. As Forrest Gump would say, “And that’s all I have to say about that.”

“Our Hearts Are Broken Today”

Yeeeaaahhhh, Boy! Cold Me-dina! LOL! (Public Enemy and The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame)

The Enemy made it! Just shows how old we all are, with Malcolm X being on a postage stamp and all…… 🙂

Will Terminator X speak at the induction ceremony? 🙂

**********

(VIDEOS BELOW ADDED ON JULY 30th, 2014)

Public Enemy – Prophets of Rage – BBC Special… by dreadinny

**********

DECEMBER 18th UPDATE: From Rolling Stone:

Chuck D on Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Of Course Hip-Hop Belongs

‘I’d like to smash the award into 10,000 pieces and hand each piece to a contributor’By Andy GreeneDecember 18, 2012 12:10 PM ETNext April, Public Enemy will become the fourth hip hop act to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Right now, however, Chuck D is extremely frustrated. He just wrapped a grueling cross-country Hip Hop Gods tour featuring Public Enemy, X-Clan, Monie Love, Schoolly D, Leaders of the New School and Awesome Dre, and he feels it didn’t receive enough attention.

“I’m perturbed at the major media for not covering us,” he says. “You didn’t hear about any tours over the last 10 years that weren’t Eminem or Rick Ross or Dre or Jay-Z or Kanye. The media was licking their ass, but we did quite well across the country and got no attention.”

Older rap acts are often called “old school,” but Chuck D thinks they need to be rebranded. “We created another genre called ‘classic rap,'” he says. “I was inspired by the classic rock radio of the Seventies. They separated Chuck Berry and the Beatles from the Led Zeppelins and Bostons and Peter Framptons of the time. In many ways, classic rock became bigger than mainstream rock.”

He also drew inspiration from an unlikely source. “I turned on the TV and saw Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus still golfing,” he says. “I’m like, ‘I thought they were retired.’ Someone was like, ‘Nah, that’s the senior circuit.’ The same thing can be happening in hip-hop. To confuse Schoolly D from Drake is absolutely ridiculous. It’s related, and there can be some interaction there, but the fan bases are different. The meanings are different. These categories protect the legacy of hip-hop.”

Classic rap artists have been playing together for years, but Chuck D was dismayed by the quality of their shows. “They were being treated like shit,” he says. “They threw a bunch of artists on a bald stage. People would come, see a bunch of old records and go home. I realized there had to be a better way to do this. I called up a bunch of people personally and told them the idea for this tour is that nobody is bigger than anybody else. It’s like what Ozzy Osbourne did with Ozzfest. We have a great camaraderie between the artists. We put 33 people on two buses and we all had the same agenda.”

The first Hip Hop Gods tour just wrapped with a show in Los Angeles, but Chuck D is already planning five more for 2013. “I’m not physically going on all of them,” he says. “I’m going to orchestrate them, and my team will actually be an integral part of them. I won’t let them become a circus, which has happened to tours in the past. If you look at hip hop touring now, it’s practically nonexistent. There’s a lot of one-offs like Rock the Bells, but a tour that goes east to west, north to south, 3,000 miles, it’s a different kind of animal.”

In the meantime, Chuck D is extremely gratified that Public Enemy are entering the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame next year. “I’m very fortunate to be acknowledged by my peers,” he says. “I take this very seriously. I grew up as a sports fan, and I know that a hall of fame is very different than an award for being the best of the year. It’s a nod to the longevity of our accomplishment. When it comes to Public Enemy, we did this on our own terms. I imagine this as a trophy made out of crystal. I’d like to smash it into 10,000 pieces and hand each piece to a contributor.”

Chuck D has little patience for people who say hip-hop acts don’t belong in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. “Hip-hop is a part of rock & roll because it comes from DJ culture,” he says. “DJ culture is the embodiment of all genres and all recorded music, if you actually pay attention to it.”

Public Enemy will be inducted into the Hall of Fame on April 18th at a Los Angeles ceremony alongside Rush, Heart, Randy Newman, Donna Summer and Albert King. “We guarantee we’re going to tear that damn place down,” says Chuck D. “I might tell DJ Lord to rock the beginning of ‘Tom Sawyer.’ Then people will be shaking their heads like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ That’s the ability of what I consider probably one of the greatest performing bands in hip-hop history. It’s not bragging, because I don’t brag about myself, but my guys are the best in the business. There’s nobody that can touch Flava Flav. There’s nobody else like him in the world.”

There’s been no talk of any onstage collaborations with any of the other artists, but Public Enemy has a long history of working with rock groups. They recorded a new version of “Bring the Noise” with Anthrax in 1991, toured with U2 in 1992 and recorded “He Got Game” with Stephen Stills in 1998.

“The goal was to enhance [‘For What It’s Worth’], to take it to another level,” Chuck D says. “I totally hate when somebody takes a classic and desecrates it. I like Jimmy Page and P. Diddy, but what they did to ‘Kasmhir’ was a debacle. They are giants in their own way – and you can print this – but that was a fucking travesty. When I get involved with a classic, I knock the fucking ceiling out of it or I leave it the fuck alone.”

A Walk Around The World…………..

…………for longform, narrative magazine journalism, “slow journalism!” GREAT idea! Hmm………

HARI SREENIVASAN: Paul Salopek is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who has immersed himself in his reporting. From riding a mule across Mexico to canoeing down the Congo, he’s been a committed foreign correspondent.

But beginning next month, Salopek will embark on a 21,000-mile walk from Africa to Patagonia, tracing the ancient path of human migration. The journey, sponsored in part by “The National Geographic,” will take an estimated seven years to complete.

Paul Salopek, thanks for joining us.

PAUL SALOPEK, National Geographic fellow: Good to be here.

HARI SREENIVASAN: So, the first question most people ask is, why?

PAUL SALOPEK: Storytelling. That’s the bottom line of this walk. It’s not an athletic event. It’s not an endurance feat. It’s all about communicating in the 21st century, slowing people down.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And so why that slow journalism? Is it something — is it a reaction to what you have seen and the speed of Twitter and Facebook and everything else?

PAUL SALOPEK: I’m not against Twitter or Facebook. I think they’re wonderful ways of getting information around.

But I’m interested in long-form journalism, long-form storytelling. And I worry about finding a space for them in today’s world, stories with beginnings, middles and end. So if I slow down stories to three miles an hour, let’s see if people follow along.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And what kind of updates are we going to see from you? I know there’s one big National Geographic story per year, but in between, what kind of — how are you going to be updating us?

PAUL SALOPEK: We have a joint Web portal between all of my partners, outofedenwalk.com, where there will be episodic reports. There will be reports that come up as the human topography merits it.

If it’s a great story, the story will surface. But what I won’t be doing — at least I don’t contemplate doing it — is micro-blogging the Johnny. I think that would get boring very fast. I will save the good stuff, gather the string, and then spring it on people.

HARI SREENIVASAN: So, what are the topics that you are interested in covering?

PAUL SALOPEK: Stories that I have covered in the past, climate change, conflict, economic development, local innovations. I’m interested in finding local solutions to big problems, stories that don’t get told because we’re moving too fast to see them.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And so this is, as we mentioned, a seven-year trip. And when we take a look at that route, you’re leaving Africa, going through Central Asia, up around China, across the Bering Strait — I’m assuming you’re taking a boat there — and then down through the Americas.

PAUL SALOPEK: Yes.

HARI SREENIVASAN: One of those, as I’m noticing, the straight line goes right through Iran. How are you going to get through that?

PAUL SALOPEK: I think that, Iran, straddles an ancient migration path into Central Asia. And, ideally, it would be wonderful to set off on foot across Iran.

I’m going to see what relations are like in late 2015. Hopefully, they’re well enough, good enough, to allow me to go through Iran.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And if there’s a necessary detour, how long does that take to get around?

PAUL SALOPEK: It’s a big place to walk around.

Part of the beauty, I think, of this long project is that there are going to be obstacles that I don’t know answers to about how to get around them until I get there. And we will see.

Serendipity is a big part of this project.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And what are the types of steps you have been taking? You have been planning this for the last couple of years. So, what are we talking about, visas, immunizations? What else?

PAUL SALOPEK: There’s a lot of logistical planning that’s gone into getting mainly governments comfortable with somebody walking through their territories. It’s an unusual request, as you might imagine.

But a lot of it also is just finding the stories en route, pre-reporting them, and, frankly, leaving some of it open. Don’t overplan it, because when our ancestors dispersed out of Africa, they didn’t have a map. They didn’t have a plan. And so we’re kind of matching that spirit.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Now, you’re doing something interesting. I read that you are going to be doing these transects every hundred miles. Explain what those are.

We have got a couple videos of them, but what are we seeing?

PAUL SALOPEK: Basically, as well as the long-form literary writing that I hope to do episodically, every 100 miles along this 21,000-mile route, I will be stopping to take a set of narrative readings, whether it’s a 360-degree panorama of the Earth’s surface, a recording of the ambient sound of the Earth’s surface, a photograph of the sky, a photograph of the surface of the Earth, to create these shards in a larger mosaic that will give basically a picture, a slice of life on the surface of the Earth at the turn of the millennium.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And you’re carrying everything. There’s not a huge SAG wagon, so to speak, in ultra-marathon race terms. Everything you have got is going to be on your backpack and you’re just hiking.

PAUL SALOPEK: That’s correct.

The idea is to go light, to — and the trend in technological miniaturization is going in my direction. Things are getting smaller. The kind of communications gear I will be carrying now will be obsolete by the time I’m halfway through, and that’s part of the story, too.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Yes.

And I think that some folks are going to be concerned about your physical safety from other humans, but I’m also as concerned about your biological safety. What are you going to be taking with you? Antibiotics? Any other precautions? You’re eating and drinking whatever is available out there.

PAUL SALOPEK: That’s right.

The idea is to live close to the ground, to eat what local people are eating. All I can say is that I have sort of — I have had a background, 15 years of living around the world, where I have got a pretty good immune system. I have got a pretty good stomach. I will be taking a small med kit with the usual antibiotics, et cetera.

Preventive medicine is going to be the key here, because I cannot carry a pharmacy on my back.

HARI SREENIVASAN: And what about — what about safety the old-fashioned way? Who’s looking out for you? Who’s got your back in case you do run into a sticky situation?

PAUL SALOPEK: I have got a collection of friends and supporters back here, not just National Geographic but The Knight Foundation, the Nieman Foundation at Harvard, the Pulitzer Center, who will be helping me basically navigate these trouble spots, if there are new ones along the way that I’m not aware of.

HARI SREENIVASAN: So, we’re raising your awareness. There are other people around the world that are.

What is the danger here in potentially becoming a celebrity? I call it the Forrest Gump effect. There you are running along. You just start to pick up more people along the way. How are you going to deal with that?

PAUL SALOPEK: It’s a really important — it’s a conundrum, because my reporting method is observational, quietly watching the world unfold around me, getting into people’s lives.

And for them to admit me in their lives, I have to be quiet. I have to listen. If this becomes too much of a spectacle, I can’t work. And so I’m still figuring this out. In today’s wired world, how anonymous can I be? I am on TV, after all.

HARI SREENIVASAN: All right.

(LAUGHTER)

HARI SREENIVASAN: That’s right.

We are going to continue this conversation online with more of your questions.

Paul Salopek, thanks so much for joining us.

PAUL SALOPEK: It’s a pleasure to be here.