Read it and see.

Monthly Archives: May 2014

ELECTION ANALYSIS: Ras Baraka Becomes Mayor of Newark, New Jersey By Earning It

The corrected, corrected version. 🙂

NEWARK, N.J.—Ras Baraka, one of the sons of the late poet/playwright Amiri Baraka, handily beat rival Shavar Jeffries Tuesday night to become the next mayor of his father’s city. How he did it was no mystery to those paying attention.

The mayor-elect paid tribute to his father, who died in January, and his mother, Amina Baraka, who was nearby off-stage at the Robert Treat Hotel here.

“I know that my father’s spirit is in this room today, that he is here with us, and I want to say ‘Thank you’ to him for believing in me up into his last days of his life, and him passing out flyers even on his hospital bed. He fought all the way to the end,” he said to his jubilant supporters.

To Amina Baraka he said, “Happy Mother’s Day, Ma. You deserve this more than me. My mother’s whole life has been Newark. She has struggled and fought, and even (fought) with all of us to make sure we go right and do right by the city of Newark.”

Using unofficial Essex County Clerk’s Office results available at deadline, Baraka’s vote total was 23,416 (53.73 percent of the vote) to Jeffries’ 20,062 (46.03 percent).

“Today we told them, all over the state of New Jersey, that the people of Newark are not for sale,” he said, referring to the estimated $2 million that Jeffries’ financial supporters, many of them anonymous donors, poured into his rival’s campaign.

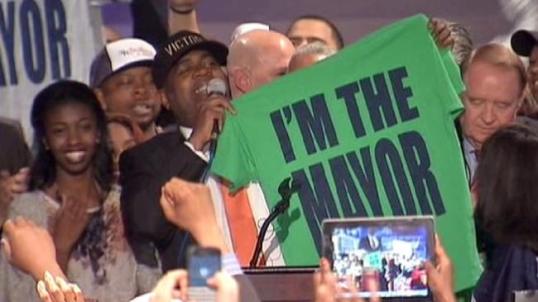

Baraka threw shirts to his supporters that read, “I’m the mayor.” His slogan was, “When I become mayor, we become mayor.” He told the crowd to celebrate, and then get ready to “roll their sleeves up and get ready to be the mayor.”

The mayor-elect and the hundreds of supporters then left the hotel and marched to Newark City Hall.

Baraka, 44, will become Newark’s 40th mayor at his July 1 inauguration.

Newark, an overwhelmingly Democratic city, has no party primary, with officials instead elected on citywide tickets. This situation allowed Jeffries and Baraka, both Democrats, to slug it out over who was best qualified to reduce crime, spur the city’s economic development and fight to repair the city’s struggling school system, the latter controlled by the state for the past 19 years.

The election is seen as important because Newark is the heart of predominantly Democratic Essex County, an important collection of votes for anyone running for New Jersey governor.

Since Newark elections have now been populated by candidates relatively new to the city, the prickly question of “authenticity” has become a real one here in the last 20 years.

A mayoral candidate now has to prove himself sufficiently Black (and soon, sufficiently Latino), urban and progressive. U.S. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), the previous mayor, promised new energy and new investments, but he still had to earn his way from Yale Law School to the Newark City Council, and eventually the mayor’s chair, vote by brick.

When the mayoral race narrowed to two, Baraka kept jackhammering at the main fault line of the Shavar Jeffries campaign: its open hubris.

Jeffries may have been born in Newark, but he appeared from Seton Hall University Law School fully formed and fully funded—by anonymous donors. Jeffries served on the Newark Advisory School Board and was president of the Newark Boys and Girls Club, two very important city positions.

But that just doesn’t carry the same juice as being on the council, where a councilmember is directly responsible for Newarkers’ lives and where people test his or her power and commitment to the city’s decaying working-class neighborhoods and the people who live in them.

The campaign had the atmosphere of history around it because of the obvious question: could the son of Amiri Baraka, a Black communist poet and playwright who was beaten by police during the 1967 Newark insurrection, be elected Newark mayor?

Until his transition into ancestry this past January, Amiri Baraka was known as a living legend in Black literature, and an historic figure in 20th century Black politics. But to many Newarkers on the street for decades, he was known as “that Black radical” and that old, cranky guy who sponsored poetry and jazz concerts in the basement of his home or in downtown city parks.

The question became less significant the more time spent on the Newark streets. Baraka received no “sympathy vote” because of his father (or his slain sister Shani, for that matter). Newarkers who were interviewed kept mentioning that they knew, or knew of, Baraka and didn’t know Jeffries.

As a deputy mayor, he accepted only a salary of $1, rejecting the doubling of his school district income. At the last debate, he said that, as mayor, he will actually receive a pay cut from his combined council and high school principal posts.

People on the street notice things like that. They also know well their elected representatives, children’s teachers and principals, and the principles all hold.

The radical Howard University student activist who returned to Newark and became a city schoolteacher, and later vice-principal and principal, taught outsiders, and reminded returning sons, that many, many Newarkers are actually committed to living here.

That radical faith in maintaining and renovating the old bricks of his city, like the younger Baraka’s ability as a poet, may be partly hereditary, but, in the end, he earned every vote he got every day between his 1991 Howard graduation and Tuesday night.

Newark, Election Day Is Here! So, One Question: What Happened To The $100 Million That Mark Zuckerberg Gave To Newark Schools?

(Articles like this one show why we still need longform, narrative journalism.)

Asante Sana, Jessica Cleaves

It’s probably only the most hardcore EWF fans who remember that there once a female lead singer of that group. Jessica Cleaves was that singer.

Jet Magazine Online Only?!? WTF?!?

So what are every liquor store and 7-11 in every ghetto going to sell? 🙂 What will be in the stack of magazines at the barbershop? This is terrible, albeit understandable, news. 😦

So what are every liquor store and 7-11 in every ghetto going to sell? 🙂 What will be in the stack of magazines at the barbershop? This is terrible, albeit understandable, news. 😦

Ras Baraka Fights a Historic Tide in Newark Mayoral Race

I’ve made some corrections to this since the first version went out to the Black press yesterday.

SOUTH ORANGE, N.J. – History keeps colliding with the present as Ras Baraka, a Newark city councilperson and city school principal, is exactly one week away from finding out if he will become mayor of Newark, New Jersey’s largest city.

In a press conference in front of his campaign headquarters Tuesday, Baraka accused his opponent, Seton Hall University Law School professor Shavar Jeffries, of openly being supported by outsiders who are attempting to buy the Newark election. He spent a lot of time talking about Newark First, an independent group that has poured almost $2 million into Jeffries’ coffers.

Newark First, charged Baraka, is aligned with Education Reform Now, a group out of New York City that pushes for the creation of charter schools.

A Google search at deadline for Newark First resulted in no website. Education Reform Now describes itself on its website as “a non-partisan 501c3 organization (that) is committed to ensuring that all children can access a high-quality public education regardless of race, gender, geography, or socio-economic status.”

Much of this election is based on who is going to control education in the city. Since 1995, the state has controlled the Newark school district, and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s appointed Newark superintendent, Cami Anderson, is, like Christie, much maligned here.

Baraka, calling the situation with Newark First “a money laundering scheme,” complained that most of the group’s money was given to Jeffries by anonymous donors. “Shavar Jefrries has raised more than any person in the race. We’re not upset that he raised more money. We’re upset that we don’t know where the money is coming from.”

The press conference came hours after Jeffries, standing in front of Newark City Hall, accused Baraka of accepting $4,400 in “pay to play” campaign contributions from companies in no-bid contracts with the city over the past two years. Baraka denied the charges in a newspaper interview and at the press conference Tuesday, saying that the contributions were well within the city’s executive order and that those who donated, according to the law, can’t do business in the city for a year.

Amid the charges and counter-charges, and the heckling of the rival campaign at each other’s public events, a name Baraka mentioned set off my historical Spider-Sense: Adubato. Baraka mentioned that the Jeffries campaign was aligned with both Newark First and “the Adubato machine.”

I first thought he meant Steve Adubato Jr., an influential local broadcaster, as the major power broker in Essex County, the county of which Newark is its political hub. But a friend of mine quickly corrected me: He meant Steve Adubato Sr., a major Newark power broker who was instrumental in stopping a man by the name of Amiri Baraka—the leader of the city’s Black power and arts movements and a major, national figure—from building Kawaida Towers, an African-centered cultural center and apartment complex in Newark.

The elder Baraka was stymied by the unions, Adubato Sr.’s machine and the Mafia. (Before Mayor Kenneth Gibson became the first Black mayor of Newark in 1970, the Mafia openly controlled the city.) Baraka’s political movement put Gibson in office, but as far as Kawaida Towers was concerned, Gibson’s hands were tied, Black elected city officials chose sides, and Baraka’s plans and movement fizzled.

Is history trying to at least rhyme, if not outright repeat itself? It seems so. The surnames remain the same, and maybe not just that.

Amiri Baraka died in January of this year. His legacy is his children.

The Newark mayoral election determines who will have disproportionate power in Essex County, which means the mayor will have influence in how the county will lean in state races, including the one that will replace Christie.

Newark may be a post-Black Power city in 2014, but red, black and green scraps remain amid the street debris. A large amount of people in the city are poor, and many are under-educated, but they are not stupid. They know who stands for, and against, them.

Outrage After Outrage

In Newark: Scrambled Notes No. 3

The Newark mayoral election, in pictures:

So the election is down to

vs.

Now, the former would like folks on the street to think of Shavar Jeffries as

The bottom line, with one week left: Jeffries would make a good mayor–of surounding townships/cities South Orange, East Orange or Orange. 🙂

A Belated Asante Sana To Chuck Stone

A legend among Black journalists. I never forgot the 90-minute “Like It Is” episode which profiled him almost 25 years ago. I learned a lot about journalism and Adam Clayton Powell from that program.

A legend among Black journalists. I never forgot the 90-minute “Like It Is” episode which profiled him almost 25 years ago. I learned a lot about journalism and Adam Clayton Powell from that program.

In Newark: Scrambled Notes No. 2

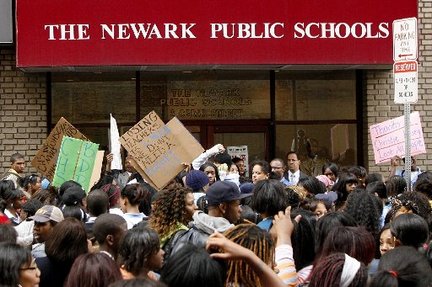

May Day in the Brick City. the People’s Organization for Progress had a march downtown (and this photo isn’t it; this is a, uh, web “file” photo 🙂 ). I began my journalistic career 29 years ago covering POP. Lawrence Hamm (far right, in the back with the gray hair), 60, has literally dedicated his life to struggle for social justice in Newark and Northern New Jersey. One of the stops on the march was City Hall, which, at least for me, had more resonance than usual less than two weeks before the election.

May Day in the Brick City. the People’s Organization for Progress had a march downtown (and this photo isn’t it; this is a, uh, web “file” photo 🙂 ). I began my journalistic career 29 years ago covering POP. Lawrence Hamm (far right, in the back with the gray hair), 60, has literally dedicated his life to struggle for social justice in Newark and Northern New Jersey. One of the stops on the march was City Hall, which, at least for me, had more resonance than usual less than two weeks before the election.

At the end of the rally, I walked the one block back to City Hall. The Ras Baraka campaign song Mrs. Baraka played for me was blasting loud. A few minutes later, I saw three people carrying Jeffries signs get into an unmarked van and drive away.

******

Thanks to my friend, teacher’s union rep Annette Alston (“charter school” is a four-letter word to her :)) , I get to meet the candidate briefly at an Ironbound restaurant. He is exhausted.

******

I go to the POP meeting (my first time in 29 years [!], since my past identity as an “objective” journalist would have felt out-of-place), and the candidate’s there, to the surprise of all gathered. He’s taking the last of a Q+A when we walk in the basement of the church that Martin Luther King spoke at the last week of his life. I hear him mention that it’s time to re-brand Newark as an international city–a name worthy of a major seaport and international airport. The nickname “Brick City” belongs to the old, industrial era, he said.

At the meeting, the GOTV effort for the candidate was discussed–who can drive folks to the polls, etc. A good May Day.