I wrote this “Drums” column in 1999, when I was a Ph.D. candidate who occasionally posted something on The Black World Today website, a now- defunct Black web pioneer.

DRUMS IN THE GLOBAL VILLAGE

A Column on Media, Race and Culture

by Todd Burroughs

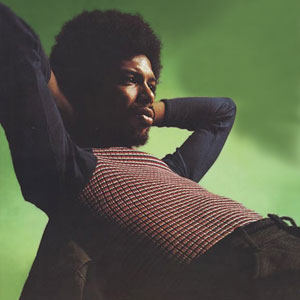

AN ‘AUTOBIOGRAPHY’ OF GIL SCOTT-HERON

I want to make this a special tribute

since I am a primary tributary and a

contributory, as it were,

to a family that contradicts the concepts,

heard the rules but wouldn’t accept

and womenfolk raised me and I was full grown

before I knew I came from a broken home

Oh, yeah!

sent to live with my Grandma down south

[wonder why they call it down if the world is round]

where my uncle was leavin’

and my grandfather had just left for heaven, they said,

and as every ologist would certainly note

I had no STRONG MALE FIGURE! RIGHT?

But Lily Scott was absolutely not

your mail order, room service, typecast Black grandmother,

On tiptoe she might have been five foot two

an in an overcoat 110 pounds, light

and light skin ‘cause she was half white

from Alabama and Georgia and Florida

and Africa.

Lily Scott claimed to have gone as far as the third grade

in school herself,

put four Scotts through college

with her husband going blind.

[God rest his soul. A good man, Bob Scott]

And I’m talkin’ ‘bout work!

Lily worked through them teens

and them twenties

and them thirties and forties

and put four, all four of hers,

through college

and pulled and pushed and coaxed

folks all around her through and over other things.

I was moved in with her.

Temporarily.

Just until things was patched.

til this was patched

and til that was patched.

until I became at

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10

the patch

that held Lily Scott

who held me

and like them four

I became one more

And I loved her from the absolute marrow of my bones

and we was holding on

I come from a broken home…..

I come from WHAT THEY CALLED A BROKEN HOME,

but if they had ever really called at our house

they would have known how wrong they were.

We were working on our lives

And our homes and dealing with what we had,

not what we didn’t have.

My life has been guided by women

and because of them I am a man.

God bless you, Mama and thank you.

*******

Man, [Latin musicians] Ray Barretto, Joe Bataan, Johnny Colon—they were like mayors in my [New York City] neighborhood [when I was growing up. After moving to New York from the South,] I was raised in what we called Little San Juan in Downtown Manhattan. It was 85 percent Puerto Rican, 15 percent white, and me. This is the music I come from. You can hear the Latin influence in [my song] “New York City”; Joe did an instrumental remake of [my signature song] “The Bottle” which was baaaadd.

Me and [basketball player] Tiny Archibald were in the same class together at [DeWitt] Clinton High School; neither of us played on the basketball team our first year; Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar] introduced me to my wife; he used to come and jam with us on the congas.

********

I suppose I really am a piano player. Because I started trying to play piano when my grandmother got this old upright that the folks next door were about to take to the city moved into our house instead. From that day when I managed to plunk out “Duke of Earl” with one finger, I was playing. But from that day in the fifth grade when our homework was to write a story and I created a three-page, three-character (wasn’t really no) mystery story, I told everybody that I wanted to be a writer. And I dropped out of Lincoln University for a year to complete the novel [my first, titled “The Vulture”], not to play the piano.

I am a Black man dedicated to expression; expression of the joy and pride of Blackness. I consider myself neither poet, composer nor musician. These are merely tools used by sensitive men to carve out a piece of beauty or truth that they hope will lead to peace and salvation.”

— From the liner notes from Gil Scott-Heron’s first album, “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox.” The song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” was a single from the 1970 album

I don’t do protest songs. I do love songs. I do the kind of songs that I do because I really care about people. I get discouraged when people think what I do is radical, especially when I talk about saving the children while folks who are considered men of peace are negotiating whether to invade Grenada or Panama or Afghanistan. What I’m talking about making this country all the things we say we are already—the land of the free, the home of the brave, the place where everybody has a chance. It’s what everybody is talking about. They just don’t have the time to make it rhyme, they don’t set it to music, but it’s the same thing.

I play [my song] “Pieces of a Man” every morning just to get my head together…..[The song is based on] this cat in my neighborhood got laid off from the one job he ever appreciated and snapped. He didn’t hurt nobody, but he was put into Bellevue [Hospital Center’s mental ward]. Everywhere I’ve traveled people [outside the U.S.] are concerned about Black Americans, ‘cause we’re still not welcome in the U.S. and we’re still here—standing. So if a man survives and comes back the next morning, then God bless, brother, and good morning to you.

Nowadays, you either hear some words thrown on top of music or some music thrown under some words, but they are not songs—they don’t go together. What Brian [Jackson] and I managed to do was make music and words that went together. Brian had a classical background and his compositions were unique. The songs said something to me, and all I had to do was to say it in words.

People ask me, “What do you call your music?,” and I say, “I call it mine.”

“Bluesology” [how I have described my music] is the science of how things feel. I come from Tennessee. The blues, that’s what time it was. That’s what color it was. There were light blues and dark blues, and you played them and they came out this way or that way, or the other way, but they were all shades of the blues.

We did something [in the middle 1970s] about [Nelson] Mandela [the song “Johannesburg”] when he was in jail. When he got out, people said, “Gil, you did ‘Johannesburg’ too soon.” I said, “Well, the brother had been in jail for 12 years [then]…..I bet he didn’t think it was too soon.”

The fact that we dared to deal with politics[–]put that up in front of the music. That was a shame. I don’t think Brian was ever appreciated as the arranger and performer he was. The flute harmonies that he created for [our songs] “Very Precious Time” and “Winter in America” and for “Back Home” were fantastic.

The music business and the record business will be your life if you get into it. You start talking in terms of “product” and “gigs.” You become disconnected altogether from human beings. You begin to think that you’re somewhere else, as though your world doesn’t have contact with the other one. I didn’t want it to feel that way. I wanted to get to know my kids. I had been divorced and didn’t know it for a couple of months. Me and my wife had been separated for about four years. The divorce papers showed up, and I was already divorced. It just showed how disconnected I had been.

*******

There are strange voices in people’s houses nowadays. People keep saying, “Oh, I get my information from the TV,” like there’s a person in there….Well, you better try to find out who’s in there.

********

Probably the original rapper was God.

In the beginning, people would ask me if I was one of the last of the poets, and I would say I guess I’m the next to the last. There is a difference between rap and what I’ve been trying to do. I do poetry, and I think there is a difference between rap and poetry.

About this “Godfather of Rap” [title the media keeps giving me] thing; I hope there’s a Godmother, ‘cos I want to talk to her about these kids.

We got respect for young rappers and the way they’re free-wayin’/

But if you’re gonna be teaching folks things, be sure you know what you’re sayin’

I have a Master’s degree from a writing seminar at Johns Hopkins University, and I spend as much time finding the right sound and the right word as I do finding the right melody and the right rhythm. I think rap sometimes has a tendency to sacrifice perspective for the beat. I try to do all I can to make sure both are correct.

I like everything the kids like, because I used to be one. I have kids myself who like it a lot, and who wonder who I am as opposed to who [rap group Public Enemy’s leader] Chuck D is. You have to give everybody some time and some experience in order for them to find their own voice. I didn’t want anyone to sum up my career when I was 20.

I like to see young people [hip-hoppers] enjoying themselves. I would rather they focus on life than death. Let them have their time. They’re just playing music like and Brian was when we started. I see some real promise there.

********

I’ve seen a lot of improvements over the years. At the time I started out, Jesse Jackson couldn’t run for his life, much less run for president. And there was no such thing as a holiday for Dr. King, there was a bounty on him. We have a tendency to overlook the good that is done to concentrate on what hasn’t been done yet. To not validate what has been done is to disrespect all the folks who did a great deal to get to this point.

Some of the people who were not open-minded in the 1960s are still not open-minded, but I think society has changed a great deal for the positive. There is more understanding between everybody. Those who learned to communicate in the 1960s are having a positive effect on young people.

As far as old people, who never wanted the communication in the first place, they’re still the folks who run things. But a lot of young folks have come to see the positive side of communications.

********

I do feel very blessed. I think The Spirits are the way to trace it. I think everyone has spirits of previous generations that help them, whether it comes from instinct or conscience or things beyond that. I think that there are certain things that have happened in my life that have allowed me to get to the point where I am.

I’ve been directly put in places, and without certain spirits moving to assist me I would not have ever had those chances. Each time I just about bottomed out , something came along to encourage me. I’ve been very fortunate. The harder I have worked, the more fortunate things that have happened to me.

I wasn’t the standard room-service artist. But this is what the spirits gave me to work with. They gave me the outrage and the manner, so to make up for it they gave me a sense of humor.

I’ve done far more with art and with stretching myself than my grandma thought I would. I have had the opportunity to perform in Europe, and to record and play all over the world. It’s almost something that brings on cardiac arrest sometimes. I got to Germany, to Switzerland, even Boston, and folks know the songs and are glad to see me, like I’m someone they’ve known for a long time. It’s a great feeling.

*********

[To be poetic] is to have a little part of the [the poem] no one understands.

(Sources: The book “So Far So Good” by Gil Scott-Heron, Third World Press, 1990; the album “Spirits” by Gil Scott-Heron and the Amnesia Express, 1994, TVT Records; 1996 comments made at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York City; “Gil Scott-Heron Pushes His Revolution” by Farhan Haq, IPS; “Full Revolution,” by Tom Terrell, XXL magazine; “Sound Check” by Bobbitto Garcia, VIBE magazine; Promotional Packet, “S.O.B.”’s nightclub, 1990; “Gil Scott-Heron is no protest singer,” by Karla Peterson, The San Diego Union, 1990; Gil Scott-Heron leaps 11 years,” by Dirk Sutro, The Los Angeles Times, 1990; “Gil Scott-Heron,” by Hank Bordowitz, American Visions magazine, 1998; “Gil Scott-Heron, Back From Being Here All Along,” by Phyllis Croom, The Washington Post, 1994; “Smoking Revolution,” by rick Glanvill, The [London] Guardian, and “Mellow Rap Fellow,” by Paul Sexton, Times Newspapers Limited.)

Compilation copyright 1999, 2011 by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D.