This is a TSB “Mumia Abu-Jamal Mixtape.” It’s a chapter for a book Michael and Annette Schiffmann asked me to write. It’s going to be translated into German. It’s my mixtape because it’s a compilation of most of what I’ve written about Abu-Jamal that’s online. Abu-Jamal will turn 57 next month, and December will mark the 30th anniversary of the Faulkner shooting.

The year 2011 was not yet two full months old, and already it was defined as one of global mass movement not seen since 1968. Tunisia. Egypt. And now, Libya—and in statehouses across the United States, as I sat writing in McKeldin Library on the campus of the University of Maryland, College Park on the last Saturday in February. Meanwhile, from a Death Row cell in Pennsylvania, Death Row journalist and author Mumia Abu-Jamal had written and distributed a column/radio commentary called “Cracks in the Empire.” I hear his voice as I read: “Despite what talking heads in corporate media proclaim, there hasn’t been a revolution in the North African countries of Tunisia or Egypt, or the Persian Gulf’s Bahrain. These have been rebellions. For revolutions transform whole societies—they just don’t remove a few leaders. That’s why much of U.S. reporting is so misleading. They want to call it a Revolution, applaud it, and freeze it, while their handpicked leaders or purchased armies seize the reins of power.”

Abu-Jamal and struggle, beginnings and endings. In 2011, it seems like he has always been around—that “Voice Of the Voiceless” from the radio and the online text. But, no, Abu-Jamal had a full and fascinating life before any “Free Mumia” website was ever created. Born Wesley Cook in Philadelphia on April 24, 1954, his voice was born at the age of 15. His story began with a discovery that galvanized him in all his parts: a weekly tabloid newspaper. Its volatile mixture of newsprint, words, drawings and pictures stirred something serious within him. The newspaper was The Black Panther, the organ of the Black Panther Party. Cook’s life—and, years later, his courtroom struggle to not be put to death—would be defined by the ideas expressed in its contents. The paper had, in effect, midwifed an activist. At a 1968 George Wallace for President rally in Philadelphia, Cook joined his friends in booing and hissing Wallace and his supporters. Some Wallace supporters became a northern lynch mob. A frantic Cook happily spied a policeman. Abu-Jamal talks about what happened next in Live From Death Row: “The cop saw me on the ground being beaten to a pulp, marched over briskly-and kicked me in the face. I have been thankful to that faceless cop ever since, because he kicked me into the Black Panther Party.”

The following year, a May Day rally was held in Philadelphia for Huey Newton, then-jailed Black Panther Party co-founder. On that day, the Philadelphia branch of the Black Panther Party—including someone now named Wes Mumia” —made its first public appearance. He described the day in We Want Freedom: A Life In The Black Panther Party: “[B]etween fifteen and twenty of us are in the full uniform of Black berets, Black jackets of smooth leather, and Black trousers…We thought, in the amorphous realm of hope, youth and boundless optimism, that revolution was virtually a heartbeat away. It was four years since Malcolm’s assassination and just over a year since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The Vietnam War was flaring up under Nixon’s Vietnamization program, and the rising columns of smoke from Black rebellions in Watts, Detroit, Newark, and North Philly could still be sensed, its ashen smoldering still tasted in the air.” The atmosphere was also tainted with the stink of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which reported on the rally and immediately opened a file on the 15-year-old.

The Party not only gave Wes Mumia Cook (as he now called himself) a second family, but also a single outlet for his creativity, his intellect and his sense of rebellion: revolutionary journalism, in the form of his post as the branch’s Lieutenant of Information. Being a propagandist suited him; Reginald Schell, his Defense Captain (the highest rank you could receive in a Panther branch, since Philadelphia’s BPP was not a chapter), noticed Cook could put words together well, both verbally and in print for The Black Panther. His Panther bylines varied with his nicknames: Wes Mumia, West Mumia, Mumia X and Bro. Mumia. His articles read like those of a recent convert (“Throughout our history, some niggers have refused to bow down and be beaten into the dust”), reflecting the defiant anger—and, some Panthers and others would say years later, the political immaturity—of the time. His articles, like most in the Party newspaper, would end with some sort of proletarian call to action: “Do Something, Nigger, [Even] If You Only Spit!” Cook had found a career that he would use to define himself as his life took many turns. School just couldn’t compete with the intellectual immersion that journalism required and the excitement it and the other Party work generated. It wouldn’t be the last time Cook would bounce back and forth between formal education and its more gregarious, dynamic, lower-class, creative, free-spirited and attention-seeking cousin. Abu-Jamal remembers in Freedom how the community was involved in selling the paper: “Throughout the early afternoon, we would get visits from school kids—not those of breakfast school age, but junior high and senior high school kids—who wanted to sell the paper in their schools. We would caution them to be careful, to only take as many as they were fairly certain they could sell, and ask them to return to the office to the office 20 cents on each paper sold before the week was out.”

All along, the Bureau followed his every move, taking down his every word—even when he left the Party in late 1970, got a GED and began attending Goddard College. But as with high school, Goddard couldn’t hold his attention. His voice found its own space: The radio.

Mumia Abu-Jamal, as he now began to call himself, learned radio broadcasting in the early 1970s by utilizing well his college stints at Goddard College’s tiny station, as well as Philadelphia’s WKDU-FM and WRTI-FM, the radio broadcast services of Drexel and Temple universities, respectively. By 1975, he was named news director at WHAT-AM, a Black-oriented commercial music station. In doing so, he became part of the first generation of fulltime salaried Black radio newscasters, charged with roaming the Black community during the day for news and events. In addition to his WHAT work, the dreadlocked Abu-Jamal hosted a show on WCAU-FM, another Black-formatted commercial station, and freelanced as a Philadelphia correspondent for two of the three recently-created Black-oriented radio news networks: National Black Network and Mutual Black Network. Abu-Jamal joined Black radio when it had became the center of political socialization for the Black community, but there was a drawback: it didn’t pay well. So he also took a part-time job as a weekend newscaster for WPEN-FM, a Top 40-radio commercial station, with that station’s management changing his on-air name to “William Wellington Cole” because it considered his new name (“Mumia” for the name of a legendary Kenyan king, and “Abu-Jamal,” which in Arabic means “father of Jamal”) too “ethnic” for the station’s white listenership.

He joined WUHY (now WHYY), the Philadelphia affiliate of National Public Radio, in 1979, becoming a featured reporter for the station’s weekday afternoon local newsmagazine, “91 Report.” By the time he got there, NPR, an outlet created for news and educational programming that didn’t have to follow commercial dictates, was establishing itself as a serious contender for agenda-setting national power as a worldwide nonprofit news source, a la the British Broadcasting Corporation. NPR grew from primarily a producer and distributor of programming into a full network, with a number of affiliate public radio stations now becoming member stations. NPR’s daily newsmagazine, “All Things Considered,” was, and still is, the network’s signature program. “91 Report” was a local news program in the format of “All Things Considered.”

Abu-Jamal, one of a very small group of African-Americans working for a NPR station, had an industry-wide reputation in Philadelphia for being an excellent writer blessed with a perfect-pitch baritone. But his penchant for editorial independence would not serve him well outside of WHAT. He covered many stories for “91 Report,” including a protest by Black concert promoters who claimed white promoters were shutting them out of booking Black artists for major venues in Philadelphia. But WUHY’s news director fired him in 1981 because he felt Abu-Jamal had become too close to the MOVE Organization, a radical naturalist group, and was no longer practicing unbiased reporting about it.

So, his voice faded by the status quo and his unswerving devotion to MOVE, Abu-Jamal—ironically, just finishing a stint as president of the Association of Black Journalists of Philadelphia, a precursor and local affiliate of the National Association of Black Journalists—began driving a borrowed cab. While driving the cab in the early morning of December 9, 1981, Abu-Jamal saw his brother, William Cook, and a Philadelphia police officer, Daniel Faulkner, in each other’s face on a city street. Abu-Jamal ran toward the two men. Guns were fired. Abu-Jamal and Faulkner were shot, with Faulkner dying at that corner. Abu-Jamal’s gun was found at the scene. Books were filled on what happened that night, with zealots and conspiracy theorists on the left and law-and-order types on the right have argued about the rest.

He was brought in front of Common Pleas Court Judge Albert Sabo, a former member of the city’s Fraternal Order of Police and the National Sheriffs Association. Amnesty International reports that Sabo “presided over trials in which 31 defendants were sentenced to death…. Of the 31 condemned defendants, 29 came from ethnic minorities.” (In 2001, Abu-Jamal’s attorneys produced a sworn statement from a court stenographer who said she overheard Sabo saying he would help the prosecution “fry the nigger” during the trial. Sabo had denied this before his death two years ago, and the claim was ignored by Philadelphia’s District Attorney’s Office.) Only two Blacks remained on the 12-member jury after the prosecution removed most of the African-Americans from Abu-Jamal’s jury pool. Abu-Jamal’s demands to have MOVE founder John Africa serve as co-counsel while he defended himself were refused. Sabo took away Abu-Jamal’s right to defend himself—took away his voice in the trial—after the defendant continued to protest. Abu-Jamal had no prior criminal record. He was convicted of first-degree murder.

During the trial’s sentencing phase, the prosecution emphasized Abu-Jamal’s Black Panther past-effectively throwing his teenage Panther voice—recorded for posterity in a front-page Philadelphia Inquirer article—back at him in front of the nearly all-white jury.

—–

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, July 3, 1982. Trial transcript, with some added-on written commentary by Abu-Jamal and Abu-Jamal trail book authors:

JOSEPH McGILL, Prosecuting Attorney: What is the reason you did not stand when Judge Sabo came into the courtroom?

ANTHONY E. JACKSON, Defense Attorney: Objection.

PHILADELPHIA COMMON PLEAS COURT JUDGE ALBERT F. SABO: Overruled.

MUMIA ABU-JAMAL, from 1982: Because Judge Sabo deserves no honor from me or anyone else in this courtroom because he operates—because of the force, not because of right.

(STANDS UP)

Because he is an executioner. Because he’s a hangman, that’s why.

McGILL: You are not an executioner?

[Abu-Jamal had no record of violent conduct prior to the Faulkner shooting.]

ABU-JAMAL: No.

(SITS DOWN)

Are you?

McGILL: Mr. Jamal, let me ask you if you can recall saying something sometime ago and perhaps it might ring a bell as to whether or not you are an executioner or endorse such actions: “Black brothers and sisters—and organizations—which wouldn’t commit themselves before are relating to us Black people that they are facing—we are facing the reality that the Black Panther Party has been facing, which is–”

Now, listen to this quote:

You’ve often been quoted saying this: “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Do you remember saying that, sir?

ABU-JAMAL: I remember writing that. That’s a quotation from Mao Tse-Tung.

McGILL: There is also a quote—

ABU-JAMAL: Let me respond, if I may?

McGILL: Well, let me ask you a question.

ABU-JAMAL: Let me respond fully. I was not finished when you continued.

McGILL: All right, continue.

ABU-JAMAL: Thank you.

McGILL: Continue to respond, then, please, sir.

ABU-JAMAL: That was a quotation of the Mao Tse-Tung of the Peoples Republic of China. It’s very clear that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun or else America wouldn’t be here today. It is America who has seized political power from the Indian race—not by God, not by Christianity, not by goodness, but by the barrel of a gun.

MICHAEL SCHIFFMANN, Mumia Abu-Jamal Biographer: [T]he fact that this statement referred to the behavior of the police in Chicago and elsewhere [in 1969] and was by no means intended as a political guideline for BPP practices did not deter prosecutor Joseph McGill from first introducing it into the evidence and then, in his summation where he argued for the death penalty, using it to stress the [so-called] violent mentality of the defendant.

McGILL: Do you recall making that quote, Mr. Jamal, to Acel Moore [a reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer]?

ABU-JAMAL: I recall quoting Mao Tse-Tung to Acel Moore about 12 to 15 years ago.

McGILL: Do you recall saying, “All Power To The People”? Do you recall that?

ABU-JAMAL: “All Power To The People”?

McGILL: Yes.

ABU-JAMAL: Yes.

McGILL: Do you believe that your actions as well as your philosophy are consistent with the quote, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”?

ABU-JAMAL: I believe that America has proven that quote to be true.

McGILL: Do you recall saying that, “The Black Panther Party is an uncompromising Party, it faces reality”?

ABU-JAMAL: (NODDING HEAD) Yes.

ABU-JAMAL, from 1993, from a Death Row cell: He [McGill] cross-examined me on that article. What you had was the sudden introduction of the Black Panther Party into a case in which it didn’t fit. The political nature is evident. If the jury were not predominately white, middle-class, older, in their fifties; if they were young people, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, who had knowledge of the current contemporary history of Philadelphia, “Black Panther” would have had a different kind of impact. The words “Black Panther” mean different things depending on peoples’ perspective, their history, their political orientation. There is a generation in America for whom the Black Panthers were not a threat but a lift, a sign of hope for a time. For another generation and class in America the Black Panthers were a threat. The prosecutor knew that exceedingly well, because that was used to bring back the death penalty. When it hit the jury it was like a bolt of electricity.

ABU-JAMAL, from 1982: Why don’t you let me look at the article so I can look at it in its full context, as long as you’re quoting?

[Abu-Jamal reads the article, dated Sunday, Jan. 4, 1970. He identifies a picture of himself and his old identity, “West Cook, Communication Secretary for the Philadelphia Chapter, Black Panther Party.” In an attempt to give the jury the full context, he attempts to read the entire article out loud. He reads his quoting of Mao. McGill interrupts.]

McGILL: So that is a quote [of yours], isn’t it?

ABU-JAMAL: “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

McGILL: Mr. Jamal, is that a quote or is it not?

ABU-JAMAL: Can I finish reading?

McGILL: Well, is it a quote or isn’t it?

ABU-JAMAL: Can I finish reading it?

McGILL: Well, will you answer the question?

ABU-JAMAL: Didn’t I ask if I could read this in its entirety?

McGILL: Will you answer the question? Are there quotation marks there?

JACKSON: Your honor—your honor—your honor—

ABU-JAMAL: Will you stop interrupting me?

[Abu-Jamal wanted to represent himself at his trial, and wanted John Africa, the founder of MOVE, to be named his co-counsel. During the trial, Sabo continually refused the second request. After several confrontations with Abu-Jamal over this issue, Sabo eventually withdrew Abu-Jamal’s power to act as his own attorney. Abu-Jamal was not at all happy with Jackson, his court-appointed attorney, and was not afraid to show it. Nevertheless, Jackson continued to defend Abu-Jamal.]

JACKSON: He already agreed to let him [Abu-Jamal] read it. May he read it?

ABU-JAMAL: If you want to go over it after I finish, that’s okay.

McGILL: Would your honor rule?

SABO: Let him read it.

McGILL: Okay.

[Abu-Jamal continued to read the article, written in the aftermath of the FBI’s war on the Party in 1969. At the time of this article’s publication, the blood of Chicago Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, assassinated by authorities, was barely dry; the Inquirer article was published one month to the day of Hampton and Clark’s murder. Moore wrote: “Murders, a calculated design of genocide and a national plot to destroy the Party leadership is what the Panthers and their supporters call a bloody two-year history of police raids and shootouts. The Panthers say 28 Party members have died in police gunfire during that period, {with} two {in the} last month. Police who have had officers killed and wounded by Panther gunfire deny there is a plot. Police have been shot at, they say simply, and they have shot back. Nevertheless, the gun battles and arrest of Panther leaders have convinced the Black Panthers that is it a party under siege.”]

McGILL: Mr. Jamal, let me ask you again, sir, if I may—If I may ask a question, Judge—was that or was that not a quote you made to Acel Moore?

ABU-JAMAL: That was a quote from Mao Tse-Tung.

DAVE LINDORFF, Author/Journalist: He [McGill] got more [ammunition] than he needed from the article. All he needed to do now was to get Abu-Jamal on the stand to state that he still held the views that he had expressed—or seemed to have been expressing if taken out of context—in that 12-year-old article. But at that point, Abu-Jamal finally caught on to his plan and refused to play.

McGILL: Is that one that you have adopted?

ABU-JAMAL: Say again?

McGILL: Have you adopted that as your philosophy theory?

ABU-JAMAL: No, I have not adopted that. I repeated that.

[Shortly after this exchange, Jackson addressed the jury.]

JACKSON: Generally speaking, you have heard character witnesses testify on behalf of Mr. Jamal. The Commonwealth has just had Mr. Jamal to read a statement that he had given perhaps 12 years ago, and Mr. Jamal indicated that he was a member of the Black Panther Party. When he further indicated that he was concerned about the Black community—that is not a concern, unfortunately, of a lot of people. By and large the concern, the interest in the Black community is left with those persons who have an interest in the Black community. Black persons. Black persons who are not at all intimidated by what the system has forced upon them…. For some time in the past at least, the white community has simply been afraid of the words “Black Panther.” That was seemingly an attitude of the white people. It was almost as if it was [a Black] Ku Klux Klan, [a similar organization of] the Black people.

DANIEL R. WILLIAMS, Author/Mumia Abu-Jamal’s lawyer from the 1990s: To many middle-class whites in Philadelphia, Mumia’s involvement in the Black Panther Party was of a piece with his sympathies for MOVE. Media profiles of Mumia lumped MOVE in with his teenage membership in the Black Panther Party, dodging discussion of the details of either organization or of Mumia’s particular involvement in them. It was enough simply to mention the two organizations, allowing them to intersect in the personage of the arrested journalist so as to propagate an alluring portrait of a dangerous Black radical fully capable of killing a soldier of the status quo.

JACKSON (continuing his statement to the jury): But what is it? How much do you really know about the Black Panther Party? Simply because they repeat—as Mr. McGill asked Mr. Jamal—simply because they repeat what someone else, Mao Tse-Tung, may have said sometime ago, can we deny that political power in America was the result of a gun? We know that we fought Great Britain. We know that we fought Indians, and we fought and we fought and we fought. And we’re still fighting in this world. Does that in and of itself indicate that Mr. Abu-Jamal is [advocating] violence? I think not, the article went on to state that the [Philadelphia] Black Panther[s], along with Mr. Jamal, fed 80 Black kids daily. Can any of you—and I don’t say this in criticism—but can any of you say that you fed 80 Black kids each day? Those Black kids needed to be fed. So the reality of the Black Panther Party, the reality of Mr. Jamal’s interest, the reality of Mr. Jamal’s activities presented to you now for which you are to judge whether or not this man is to receive the [death] penalty or life imprisonment.

[After Jackson was finished, McGill gave his final statement to the jury. He discussed Abu-Jamal’s almost constant defiance during the trial as yet another example of the need for law and order. Faulkner, the slain officer, represented this need, declared McGill. Discussing the defendant’s contempt for his own attorney, the prosecutor said Abu-Jamal saw Jackson as a “traitor” because Jackson was representing and following the law.]

McGILL: Again, this is what this is all about, law and order. How do we avoid it if we don’t like it, we don’t just accept it, and we don’t try to change it from within, we just rebel against it. And maybe that was the siege all the way back then with political power, power growing out of the barrel of a gun. No matter who said it, when you do say it and when you feel it, and particularly in the area when you’re talking about police and cops and so forth, even back then, this is not something that happened over night.

WILLIAMS: McGill, the one who first gave voice to the hard-line anti-Mumia perspective [that exists today], had no interest in learning about Mumia’s life to gain insight into his political and moral beliefs. He simply extracted from a 1970 newspaper article a Mao quote that was fashionable among Black Panther members at the time and wove a story around it. Mumia’s affiliation with the Black Panther Party and his attraction to MOVE symbolized his renunciation of law and order, which is nothing more than a lazy slogan for preserving the status quo and all of the values that support it. Whether Mumia killed Officer Faulkner or not became secondary inasmuch as it was taken as a starting point for McGill. The trial, from the prosecution’s perspective, was not so much about proving Mumia’s guilt as it was about explaining it. McGill’s success in positing a compelling explanation for the killing—leaving aside whether the explanation was right or wrong—propelled the case toward its ultimate death verdict. That success still drives the anti-Mumia rhetoric….. The Panthers were indeed fond of Mao’s remark that “all political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Mumia’s early political awareness could not have sidestepped such sloganeering. But it was too much for McGill’s jury, nurtured on network news and sitcoms, to understand that the Panthers in general, and Mumia in particular, embraced Mao’s remark as an observation, a pithy distillation, of European and American history. Mumia tried to explain that point to the jury, but the transmittal of that message, occurring in Judge Sabo’s pressure-cooker courtroom with the fog of death hovering over the proceedings, was lost upon an audience that had already adjudicated Mumia a cold-blooded cop killer.

——

The jury called for the death penalty. In 1983, Sabo sentenced Abu-Jamal to death by the electric chair. Sabo sentenced Abu-Jamal to death. The last line of the transcript is Abu-Jamal saying to Sabo: “Long live John Africa! On The Move! Fuck you, Judge! Fuck you.”

Silence. Then a trickle of letters. Then an almost-forgotten chapbook of essays, Survival Is Not A Crime, mostly expressing his anger over the 1985 MOVE bombing. Then individual Op-Eds in the late 1980s and early 1990s, some of which were recorded for NPR in 1994. NPR, however, dropped its plans just days before they would begin airing on “All Things Considered” after an avalanche of right-wing criticism. Soon after, he published Live From Death Row, a full-fledged collection of his essays about prison life. The book got him put in Death Row’s equivalent of solitary confinement for, according to prison regulations, engaging in entrepreneurship. He was placed in complete isolation in 1995 after receiving a date to die only a few months later. The execution date was later suspended.

Abu-Jamal eventually won the battle to write for pay from prison, but he would lose significant skirmishes. When Home Box Office in 1996 aired the documentary “Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case Of Reasonable Doubt?,” which included a compelling interview with its subject, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections banned outsiders from using any recording equipment in state prisons. In a replay of what happened with Abu-Jamal and NPR, Temple University’s WRTI-FM, one of the station’s that Abu-Jamal first broadcast from, pulled Pacifica Radio Network’s “Democracy Now!,” the national leftist weekday radio newsmagazine, and all other Pacifica programming in 1997 when the program was about to air some new commentaries. In August 1999, prison authorities yanked the wires of Abu-Jamal’s telephone out of its wall when, for a brief time, he began doing his “Democracy Now!” commentaries live. They did so while he was on the phone, while on-air.

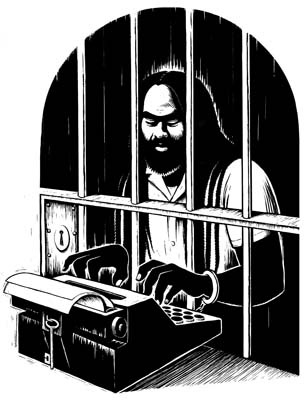

But Abu-Jamal’s voice, now fully matured, took advantage of the controversies. At the dawn of the new century, it was now heard regularly on low-power radio stations around the world. Or online. Or at concert fundraisers for his case. Or at graduation ceremonies at colleges filled with leftist students. On CDs produced by his supporters. The activist became the journalist, the journalist became the convicted murderer, and the convicted murderer became the symbol and the scholar, the object and the prism—all through the tenor and tenure of one voice. The Black voice deepened and was heard, simultaneously shattering both the silence and the noise. Guilty or innocent, it echoed from the tiny chamber of death around the world, inspiring, engaging (and, for some, enraging), a dual symbol of oppression and freedom. But for Abu-Jamal, time would continue to pass slowly, still alone in that cell.

The first Abu-Jamal column I ever read was in a New York Black newspaper in 1994. The column caught my eye because it was a tribute to Joe Rainey, a Black radio broadcaster who was an important voice of Black Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s. Rainey had recently died. Abu-Jamal took the occasion to recall his brief time on Rainey’s air as a teenage Black Panther Party member. In my Black media studies, I had never heard of Rainey. And I didn’t think I had ever heard of Abu-Jamal. (Years later, digging through piles of my junk—aah, I mean, my personal files—I would find a 1990 flyer discussing Abu-Jamal’s case.) I had no idea this broadcaster and columnist was practicing print and broadcast journalism, by hand, from a Pennsylvania Death Row cell he has said is the size of a bathroom.

That changed as the year progressed. The Source, a national monthly periodical that calls itself “the magazine of hip-hop music, culture and politics,” carried a feature on Abu-Jamal’s case. I quoted the article in a column about him for a national Black newspaper wire service, and moved on. But in 1995, the following year, Abu-Jamal was thrust into the international scene. Two events captured the media’s attention in Europe and America. The book Live From Death Row, his first, was published. The second—a death sentence that was suspended at the last minute—quickly followed. Both deeds virtually started the “Free Mumia” movement and confirmed the course of my career.

As a young person growing up in an urban area in the northeastern part of the United States during the 1970s and 1980s, I consistently heard former Black Power supporters talk about the effect The Autobiography of Malcolm X had on their lives when it was first published in 1965. I pretended to understand and relate. During the years of Ronald Reagan and George Bush The First, many young Blacks unfortunately found current truths in Malcolm’s long-uttered words. I was one of them. But although The Autobiography seemed to be about today, it was, in reality, more a defining part of yesterday. In my case, it was literally more high school book report topic than contemporary manifesto.

Then along came Live From Death Row and two tapes of Abu-Jamal’s radio commentaries, all between the beginning of 1994 and the end of 1996. The book, published after the NPR controversy, was not negatively affected by the debacle; it just received more publicity. It came out for all to see and read. I did, and was affirmed, if not transformed. I began to understand what the Black Power-era Baby Boomers were talking about, a la The Autobiography. I had found a book that, as a Black journalist in the mid-1990s, spoke directly to me—in content, in execution and in purpose. Here was a talented Black journalist not practicing Black “objectivity”—defined, in my eyes, as the art of presenting (and negotiating) Black perspectives in ways that allow Black mainstream journalists to make rent and car payments. Here was someone who apparently did not worry about receiving acceptance from, and credibility with, America’s powerful. Here was a Black writer who was clear, and not afraid to raise his voice in an undiluted way.

At the time, I was working on my third journalism degree—a Ph.D., with a research focus on Black journalism history. I had begun to accept that serious but pointed, angry Black advocacy print journalism would be found only in the microfilmed past. But with Live From Death Row, I had finally found someone who used journalism in the way I thought oppressed people should. Today. I gave away copies of the book. I read every Abu-Jamal column I could get my hands on. I played those first tapes over and over again. I subconsciously (?) began to write like him. A friend joked that I even began to try to sound like him. I began to keep a little file on this Death Row author. That file, started in my 20s during the Clinton administration at the beginning of the World Wide Web, has now blossomed into a full file cabinet’s worth of material as I, now a balding, 40ish, fulltime Communication Studies lecturer at Morgan State University, a historically Black college in Baltimore, Maryland, watch the victory celebrations in Egypt on Al Jazeera English’s live Web streaming in the Age of Obama. Time is moving fast for me.

Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Wisconsin, USA. Typewriters, PCs, laptops, Blackberrys. iPhones. Newspaper columns, blogs, Tweets. The Nation, Mother Jones, The Black Panther, Rolling Stone, In These Times, “Democracy Now!” on radio and now TV, Free Speech Radio News, Free Speech TV, Grit TV, the Real News Network, low-power radio, YouTube, and now, Facebook and Twitter. This is the speeded-up world we live in now, with millions of cascading digitized voices seeking comfort, clarity, friendship and, now, becoming witnesses and participants in either revolution or the various types of reform and resistance. Meanwhile, libraries, newsprint, cassette tapes, books, boomboxes, Walkmans, CDs, iPods, downloads, Google Books, Kindles, Apps—the long progression of Abu-Jamal’s voice. The world has changed dramatically since Noelle Hanrahan and Jennifer Beach recorded and photographed him that first time more than 15 years ago. While he has been locked away, the world’s activists have become less voiceless. Movements that rival the size, if not in substance, of the teenage Cook are now being organized by people using media themselves. Coming out of mid-20th century traditions of Black (and) radical journalism, Abu-Jamal has provided an example to follow in post-modern, early 21st century life, and we have caught up with him.

The young jailed radical is now a middle-aged leftist institution. He is well on his way to turning 60 in a prison cell, chasing life and dodging death while standing still. So what if he becomes an Elder in prison? Then he will continue down a path blazed long ago by the first African who beat a drum, Thomas Payne’s Common Sense, David Walker’s Appeal, Frederick Douglass’s The North Star newspaper, Martin Luther King’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul On Ice and George Jackson’s Soledad Brother, by radicals and writers and propagandists known and unknown. And we will continue to read his words and listen to his voice. So what if he dies by lethal injection? Then he will join those spirits, pushing the wind in the direction of change, attempting a shouted whisper of “Revolution!” in the ears of activists around the world in silent meditation.

He, and me, and you, used to be invisible, unheard and unheard of. Our thrown pebbles were unable to make any visible ripples in life’s info-ocean; worldwide-distributed text, audio and video belonged to The Powers That Be, and tweets were the exclusive property of birds. Now, the wave has come, and everyone from Death Row inmates in SCI Greene to Egyptian protesters in Tahir Square can shout in ways that will be registered. However the story of Mumia Abu-Jamal ends, he will be remembered for his determination to be heard. We will, too, if we continue the bravery that, at our best, we continually show in defiance of unjust systems.

© 2004, 2011 by Todd Steven Burroughs. All Rights Reserved.