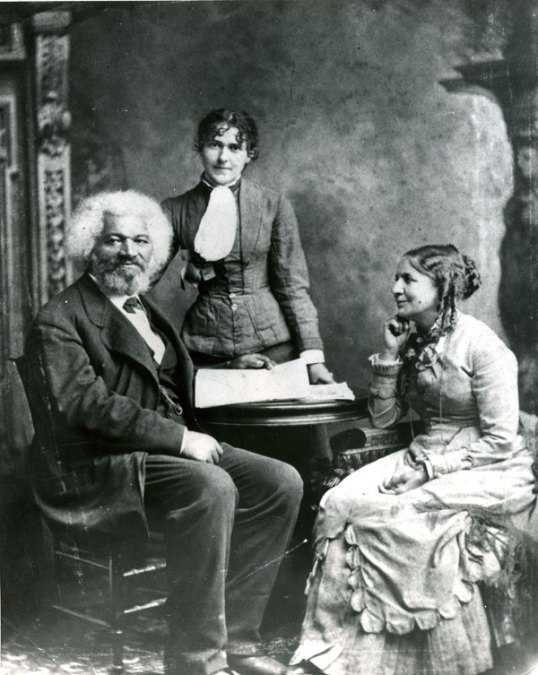

Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave.

Written By Himself.

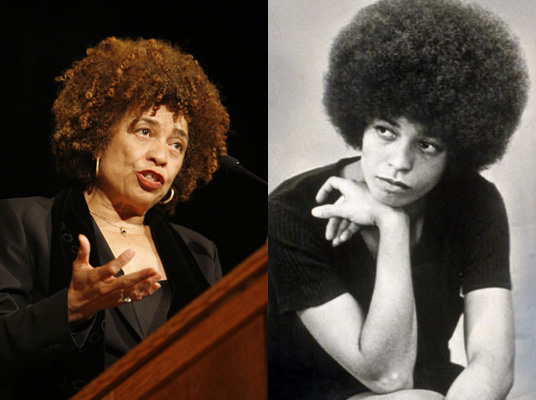

A New Criticial Edition by Angela Y. Davis.

CityLights Books.

256 pp. $12.95.

What, to the feminist, is the life of Frederick Douglass? It is a life that reveals to him and her the power of a man attempting to achieve freedom and finding that to be free meant to be free in all things—in word, in deed, in spirit. But it also means that definitions of freedom must continue to be redefined, revised, expanded.

The chains that held Douglass and Angela Davis, two of the strongest freedom fighters that America’s oppression produced, hold together the new edition of this classic work of American autobiography. Using the text of lectures she delivered at UCLA in 1969, after the university fired her for her Communist affiliation but before her world-famous arrest and trial, Davis provides an extended introduction of sorts to the world of Frederick Douglass. In her talks, she uses Douglass to examine the philosophy of freedom.

The escaped slave wrote the book to prove to all that his story was true. He also needed his story to be connected to him, not to his abolitionist friends and allies. To Douglass, writing, was like reading—an amazing power: “I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.” In a new introduction to her decades-old lectures, Davis, no stranger to the writing of a classic autobiography and to the sexism within Black movements, dissects Douglass’ strengths and pitfalls of how he defined freedom—a definition that, Davis explains, leaves enslaved women behind as symbols of oppression, unable to achieve the “manhood” Douglass equates with his liberation.

The two pioneering feminists merge together, in theory and in practice, on the nature(s) of liberation. In this book of merged centuries, freedom travels from idea to action (creating resistance) to finally, negotiating a complex reality. Davis, in 2009 : “Many of us thought [in the 1960s and 1970s] that liberation was simply a question of organizing to leverage power from the hands of those we deemed to be the oppressors.” An idea whose time has gone in the Obama era, one in which, supposedly, the ultimate power has been leveraged, but from whom and for what? This new version of an old book is a perfect excuse to analyze (Douglass’ and Davis’) views of freedom as we continue to debate the Black movement’s purpose in the second decade of the new century.