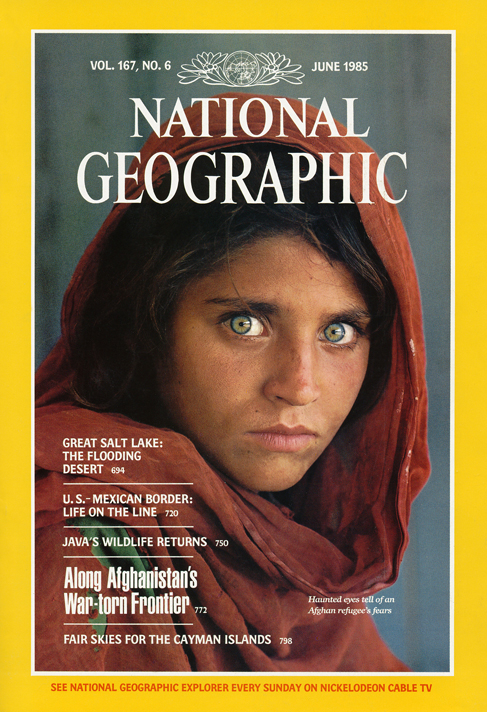

My reaction to the news about Playboy and National Geographic!

Tag Archives: National Geographic Society

Book Review: Within The Cage

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga.

Pamela Newkirk.

New York: Amistad/HarperCollins.

304 pp.; $25.99 (hardcover).

It’s the ingredients for a powerful devil’s brew: take white supremacy, slavery and colonialism and mix thoroughly with late 19th and early 20th century zoology, ethnology, wildlife conservation and taxidermy. Sprinkle with Darwin’s theory of evolution and simmer in Greater New York, the precursor to New York City. Simmer. Then pull back the curtain and pour, showing the African—the so-called “pygmy”—on public display in the monkey cage at the Bronx Zoo, all for the sake of greed disgustingly disguised as science.

Written by New York University journalism professor Pamela Newkirk in as dispassionate a tone as can be attempted, “Spectacle” shakes all the way to the reader’s core. The tale of Ota Benga, the Congolese forest dweller—exhibited with other captured people in the 1904 World’s Fair, the symbol of white world progress, and then, two years later, solo at the zoo—crackles with 21st century disbelief, even after taking into account an elementary historical understanding that many Europeans and white Americans for centuries publicly declared Blacks sub-human.

“For the general public [of the World’s Fair], the sight of barely clad, presumably primitive people assembled across the fairgrounds was evidence enough of Caucasian superiority,” writes Newkirk. “The beings whom scientists had described as semi-human, cannibalistic dwarfs were no longer regulated to mythology or to anthropological field notes. The reality—that the delegation comprised captured African children—if considered at all, was understood as merely a means to a scientific end.”

The painful, and painstakingly researched, work of social history goes beyond the surface level of “Whites Only” signs into the bleached hearts of an insecure, psychologically disturbed people who, in the early part of the 20th century, argued over the level of humanity of an African they had caged, failing to see the obvious irony. The efforts of a group of Black preachers to free Benga from his Bronx Zoo cage is prominently noted (as is the intellectual combativeness of the voice of true scientific reason, the anthropologist Franz Boas), but their limited, and relative, access to their own freedom and power dangles in the background.

Because Newkirk had no historical access to Benga, the public sensation via personal violation, she had the challenging task of writing around the man at the center of the monkey cage—the “prey for a merciless hunter.” That hunter’s name is Samuel Phillips Verner, and he is the central subject of this merciless defilement. He proves the old adage that some people in life pose as a friend in order to get into position as a more effective enemy.

Verner is, in many ways, the quintessential unapologetic white man for this type of unapologetically harsh story, fitting the perfect casting call for the benevolent white American liberal who interrupts African life for gold, status and power. He is a liar and thief who camouflages his character through the chronological guises of missionary, then adventurer, and finally an amateur “scientist” and “African expert” in this white world of European and American pseudo-science. In the histories and academic studies written and embedded by white men, he is the man who did well by doing good. Newkirk exposes his decades of shameless, opportunistic motives and behavior in what should be called visionist history.

Belgian King Leopold II’s shadow, and especially the mass graveyards of his uncounted African victims, loom over this work. Benga’s “rescue” by Verner, while the “hero” cuts business deals almost every waking hour, is symbolic of the American complicity in the raping of the continent by Europe. (As Newkirk shows, Belgium’s public relations campaign to get greedy American imperialists on its side—with Verner as one of many leaders—was quite successful, while it lasted.) The public shaming of white supremacy in the Congo by true heroes Mark Twain, George Washington Williams and Booker T. Washington are mentioned, but it is Verner’s ruthless ambitions that solidify the book’s central vortex.

Meanwhile, Benga—who a New York Times editorial charitably described as “a human being, of a sort”—resisted his captors as best he could, being a stranger in an absurd land surrounded by paternalistic friends. One day, he defies the zookeepers by physically fighting them. When he was physically prodded by the rowdy throngs that crowded the park to see him, he struck back. When he was allowed to roam the park, and another horde decided to track him, he fired an arrow at one of the rabble. He pulled a knife against a handler. Later, when he was moved to a museum, he attempted to escape. And finally, now years separated from his village, refusing to ask his former captors for help getting back to the Congo, he does what he must to ease his deepening depression. The author allows Benga’s actions to speak above the crushing waves of this psychologically tortuous history.

The Bronx Zoo, the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Natural History, the National Geographic Society and their institutional fellow travelers in quantitative academia—all historic bastions of elite, white male privilege—will have a lot of questions asked by Newkirk’s readers to answer. Complicity in the crimes against African humanity connects like amber waves of grain. “Me no like America,” Benga said from his cage.

Frederick Douglass said in a famous 1852 speech that the United States of America was guilty of “crimes that would disgrace a nation of savages.” This superb book proves that postulate again, right in time for recent, post-modern generations of Americans who seriously need to come to terms with that consistent, historical truth.